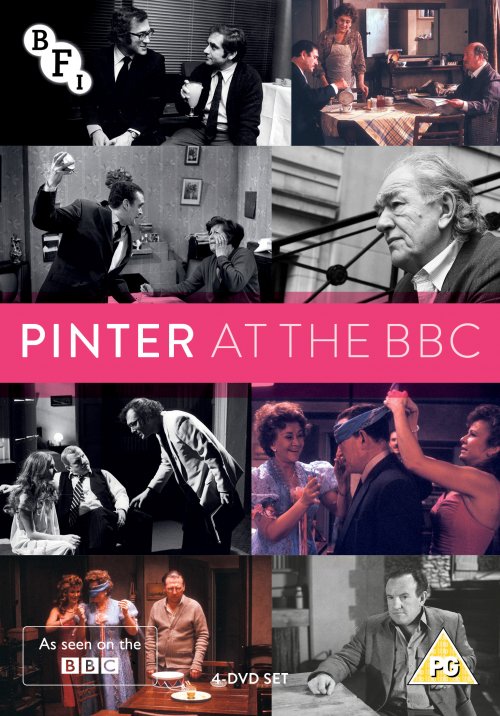

This is an incredibly welcome release, as it brings together a very healthy chunk of Harold Pinter’s BBC output (none of which has been commercially available before). Indeed, Pinter’s television work on DVD has, until now, been rather sparse (a few isolated offerings from Network – the Armchair Theatre production of A Night Out and the Laurence Olivier Presents staging of The Collection – have been the highlights so far).

Disc One

Tea Party (25th May 1966). 76 minutes

Tea Party was commissioned for a prestigious Eurovision project, entitled The Largest Theatre In The World, which saw the play performed in thirteen separate counties over the course of a single week (some took a subtitled version of the BBC original whilst others staged their own adaptation).

It’s a layered and uncompromising piece, with Leo McKern mesmerising as a self-made businessman who begins to lose his sense of reason (and also his sight). Has he been destabilised by inviting his brother-in-law Willy (Charles Gray) into his business or has his infatuation with his new secretary, Wendy (Vivien Merchant), pushed him over the edge? Do his two young sons from his first marriage really harbour evil intentions towards him or does his new wife, Diana (Jennifer Wright), possesses secrets of her own?

So there are plenty of questions, but as so often with Pinter the answers are less forthcoming. The final scene is extraordinary. Disson (McKern) – his eyes firmly bandaged – sits immobile in the middle of a party held in his honour. Although Disson plainly can’t see, we’re privy to his thoughts (he imagines a three way intimate exchange between his wife, brother-in-law and secretary) as he slowly regresses into a catatonic state.

All of the principals offer polished performances, with Merchant – Pinter’s first wife – especially eye-catching. Given the subject matter and the already rocky relationship she was enjoying with Pinter, it’s fascinating to ponder just what she made of the material. Tea Party is fluidly directed by Charles Jarrott and given that the cameras of this era were bulky and not terribly manoeuvrable, some of his shot choices are quite notable.

It’s a shame that the telerecording isn’t of the highest quality (a new 2K transfer was struck for this release, but given the issues with the original recording the benefit of this was probably minimal). A pity, but at least the worst of the print damage occurs early on.

The Basement (20th February 1967). 54 minutes

Harold Pinter contributed three plays to the Theatre 625 strand in 1967. For some reason the third of these plays appears on the first disc whilst the first two are featured on the second. That’s slightly odd, but since all three aren’t linked in any way it doesn’t matter which order they’re watched in.

We’re in absolutely classic Pinter territory here as Law (Derek Godfrey) discovers his cosy basement flat has been invaded by an old friend, Stott (Pinter) and Stott’s young and mainly silent girlfriend Jane (Kika Markham). Initially pleased to see Stott, Law is less enthused – at first – about Jane ….

The arrival of an outsider into a settled domestic setting is a dramatic device that Pinter would use time and again, but The Basement – the only one of his three Theatre 625 plays to be an original work – is notable since it plays with the artifice and techniques of television.

Even more so than Tea Party, the line between reality and fantasy becomes increasingly blurred as the play continues. Some scenes (such as when Law and Stott, both stripped to the waist, fight each other with broken bottles) seem obviously fantastical, but what of the others? Time certainly seems to move in a disjointed fashion (one moment it’s winter, the next summer) whilst the final scene posits the possibility that everything we’ve seen has been a fantasy.

Pinter is menacing and monosyllabic as Stott but not as monosyllabic as Markham’s Jane, who is passive throughout whilst Godfrey has most of the dialogue and seems to be the most decipherable character of the three. A tight three-hander, The Basement has aged well.

Special Feature

Writers in Conversation – Harold Pinter. A 1984 interview with Pinter, running for 47 minutes.

Disc Two

A Slight Ache (6th February 1967). 58 minutes

Another three-handed play which also pivots on the arrival of an disruptive outsider, A Slight Ache boasts remarkable turns from both Maurice Denham and Hazel Hughes. Husband and wife – Edward and Flora – they seem reasonably content in their country cottage, but when they invite a nameless and mute matchseller (Gordon Richardson) into their home everything changes.

Denham’s fussy, pernickety Edward is slowly destroyed by the matchseller’s ominous silence whilst Flora finds that her long-dormant sexuality has been reignited by his presence. Some contemporary reviewers found this a little hard to swallow, but realism isn’t the chief component of this play. The matchseller simply serves as a catalyst for Edward and Flora to indulge in several powerful monologues.

Despite its radio origins, A Slight Ache has a much more of a theatrical feel than The Basement. Barry Newbery’s sets (especially the lush garden) are a highlight of the production.

A Night Out (13th February 1967). 60 minutes

It’s interesting to be able to compare and contrast this production of A Night Out to the 1960 Armchair Theatre presentation. Honours are pretty much even, with Tony Selby here proving to be equally effective as the repressed mummy’s boy as Tom Bell was back in 1960.

Anna Wing, as the mother in question, makes for an imposing harridan – although wisely she doesn’t overplay her domineering nature. Albert (Selby) is all she has left, but she ensures that her psychological games comprise honeyed words and pitiful entreaties rather than abuse.

Albert’s humiliation at an office party eventually leads him to a prostitute (Avril Elgar). That she, in her own way, is just as controlling as his own mother unleashes his ugly side. All the pent-up emotions he can’t express at home are unloaded on this poor unfortunate.

Well-cast throughout (John Castle and Peter Pratt catch the eye) A Night Out is the most straightforward of the three Pinter Theatre 625 productions, but is no less fascinating.

Disc Three

Monologue (13th April 1973). 20 minutes

We’re now in colour for the fifth play in the Pinter set. At just twenty minutes it’s one of the shortest and only features a single actor – Henry Woolf, but it still packs plenty of content into its brief running time though. An unnamed man (Woolf) addresses an empty chair, which is standing in for his absent friend. Or does he believe that his friend is actually sitting there? Or is his friend simply a figment of his imagination?

As so often, several readings can be made, each one equally valid. The story which unfolds – male friendship disrupted by the arrival of a female – echoes back to the likes of The Basement and is skilfully delivered by Woolf. One of Pinter’s oldest friends (the pair enjoyed a relationship for more than fifty years) Woolf doesn’t really put a foot wrong (he later reprised this piece at the National in 2002).

This might be a Pinter in miniature, but is certainly deserving of attention. Something of a neglected piece (there’s no listing on IMDB for example) hopefully this DVD release will shine a little more light on it.

Old Times (22nd October 1975). 75 minutes

Old Times has a very theatrical feel. This form of television staging would eventually fall out of fashion – for some it was simply electronic theatre (a bad thing apparently). But it’s always been a style that I’ve enjoyed – when there’s no location filming or clever camera angles, the piece has to stand or fall on the quality of the writing and acting.

It’s another triangle story – married couple Deeley (Barry Foster) and Kate (Anna Cropper) find their status quo disturbed by the arrival of Kate’s old schoolfriend Anna (Mary Miller). With Kate remaining passive for most of the play she becomes an object that both Deeley and Anna seek to claim as their own.

Several theories have been propounded to explain the meaning of the play. When Anthony Hopkins tackled the role of Deeley in 1984 he asked Pinter for some pointers. The playwright’s advice? “I don’t know, just do it”.

Anna’s presence at the start of the play (standing at the back of the living room in darkness and immobile) is a early indictor that the production isn’t striving for realism. She shouldn’t be there – the dialogue between Deeley and Kate makes it clear she’s yet to arrive – so her presence ensures that a tone of oddness and disconnection is set. Foster and Cropper duel very effectively (a lengthy scene where Deeley and Anna discuss the best ways to dry a dripping wet Kate is just one highlight).

Puzzling in places (has everything we’ve witnessed simply been Deeley’s imaginings?) Old Times is nevertheless so densely scripted as to make it a rewarding one to rewatch.

Landscape (4th February 1983). 45 minutes

Landscape is a two-hander shared between husband and wife Duff (Colin Blakely) and Beth (Dorothy Tutin). Both indulge in separate monologues which never connect to the other person’s conversation. Beth in fact never acknowledges Duff’s presence, although he does appear to know that she’s there (or at least that someone is).

The Lord Chamberlain’s office, back in 1967, found itself unimpressed with Landscape. “The nearer to Beckett, the more portentous Pinter gets. This is a long one-act play without any plot or development … a lot of useless information about the treatment of beer … And of course, there have to be the ornamental indecencies”.

A little harsh maybe. Landscape is plotless but leaves a lingering impression. The music, composed by Carl Davis and played by John Williams, helps with this.

Special Feature

Pinter’s People – four animated short films (each around five minutes) from 1969. A pity that a fifth – Last To Go – couldn’t be included for rights reasons, but the ones we do have are interesting little curios (Richard Briers, Kathleen Harrison, Vivien Merchant and Dandy Nichols provide the voices, so there’s no shortage of talent there).

Disc Four

The Hothouse (27th March 1982). 112 minutes.

Watching these plays in sequence, what’s especially striking about The Hothouse is just how funny it is. There have been moments of levity in some of the previous plays, but the farcical tone seen here is something quite different. Originally written in the late fifties and then shelved for twenty years, The Hothouse is set in a government rest home which, it’s strongly implied, uses any methods necessary to “cure” its unfortunate patients (who we can take to be political dissidents).

Although a dark undertone is always present (indeed, the play concludes with the offscreen deaths of all but one of the senior staff) there’s also a playful use of dialogue and even the odd slapstick moment. Derek Newark as Roote, the hopelessly out of his depth manager, steamrollers his way through scene after scene quite wonderfully.

A man constantly losing a running battle to keep his anger in check, Roote seems incapable of understanding even the simplest of things. Although he may not be quite as dense as he appears (his culpability in the death of one patient and the pregnancy of another is certainly open to interpretation).

With a strong supporting cast, The Hothouse was certainly the most surprising of the main features.

Mountain Language (11th December 1988). 21 minutes.

A one-act play which was first performed at the National Theatre in late 1988, it swiftly transferred to television just a few months later with Michael Gambon and Miranda Richardson reprising their stage roles. One of Pinter’s more political pieces, Gambon and Richardson (along with Julian Wadham and Eileen Atkins) all offer nuanced performances.

Gambdon and Wadham are soldiers, facing down a group of prisoners who include Richardson and Atkins. Language, so often key in Pinter’s works, is once again pushed to the forefront.

“Your language is forbidden. It is dead. No one is allowed to speak your language. Your language no longer exists. Any questions?”

Mountain Language is another prime example of the way Pinter could make an impact in a very short space of time.

Disc Five

The Birthday Party (21st June 1987). 107 minutes.

Written in 1957, when Pinter was touring in a production of Doctor In The House, The Birthday Party was Pinter’s first full length play. Revived thirty years later for this Theatre Night production, it’s plain that time hadn’t diminished its impact.

Kenneth Cranham is mesmerising as Stanley, a man haunted by vague ghosts from his past. Treated with stifling maternal love by his landlady Meg (Joan Plowright), the arrival of two mysterious strangers – Goldberg (Pinter) and McCann (Colin Blakely) – marks the beginning of a nightmarish twenty four hours. Also featuring Julie Walters and Robert Lang, The Birthday Party baffled many critics back in the late fifties – the reason why Goldberg and McCann have decided to target Stanley and the others is just one puzzle – but in retrospect it’s fascinating to see how key Pinter themes, such as the reliability of memory, were already firmly in place.

Special Features

Face To Face: Harold Pinter. Sir Jeremy Isaacs is the out of vision interviewer since – as per the style of all the programmes in this series – the camera remains firmly fixed on Pinter throughout. Some decent ground is covered across the forty minutes of this 1997 interview.

Harold Pinter: Guardian Interview. Audio only, 73 minutes. This is selectable as an additional audio track on The Birthday Party, even though it doesn’t directly refer to that play (or run for its whole length).

It might only be January, but this looks set to be one of the archive television releases of the year. Highly recommended.

Pinter at the BBC is released by the BFI on the 28th of January 2019.

Great to see, think this will be going on my birthday list!

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] of the incisive reviews of the set that are starting to appear online is one detailed critique that is likely to remain obscure. The […]

LikeLike

On my copy of the set, disc 4 has a slightly filmised look to the VT particularly evident in movement, it’s quite distracting.

LikeLike

I remember also seeing on BBC may years ago The Dumb Waiter & The Lover (Merchant unforgettable). Any reason why these were omitted?

LikeLike

The Lover was an ITV production, so outside the remit of this boxset, but The Dumb Waiter was a surprising omission. Possibly there was a licencing or rights issue.

LikeLike