The aged Claudius opens the episode by informing us that following Tiberius’ retirement to Capri, the Empire was effectively now run by Sejanus – who, unfettered by any restraints, instigated a brutal reign of terror. Of course, by the end of the episode we’ve witnessed another reign of terror and in this one Sejanus turned out to be a victim …

As in previous episodes, Tiberius remains an isolated figure with Sejanus solely responsible for deciding who will be lucky enough to be granted an Imperial audience. On the one hand this suits Tiberius very well – he remarks this makes Sejanus the visible figure who attracts the ire of the public (with Tiberius remaining unaffected in the shadows). But there has to be another part of him that realises by abdicating so much power, he’s now little more than an impotent puppet.

Ironically, it’s his hated adversary Agrippina who articulates this very point. Even when she’s brought to him in chains, she manages to exude an aura of lofty disdain. Their final meeting is no more agreeable than any of the others – an apoplectic Tiberius whips her before she’s banished to the same island where her mother (Julia) lived out the remainder of her life.

Although he’s not given a great deal of screentime today, every single moment that John Hurt appears is a joy. Caligula’s first scene with Claudius is an instructive one – at this point Caligula may be hedonistic and totally self-obsessed, but he’s not mad (that would come later). He expresses polite disinterest in the fate of his brothers (Drusus and Nero) to Claudius’ disgust – but it’s fair to say that he’s only doing what Claudius has done all his life (keeping his head down, when all about are losing theirs).

Even better than this scene is Hurt’s deadpanning later in the episode, as Claudius brings Tiberius evidence that Sejanus and Livilia planned to murder him. Caligula’s reaction (“I always knew that woman was no good … people really are despicable”) is ordinary enough, but it’s the playful relish of his delivery that entertains so much.

It’s a rare comic highlight (as is Claudius’ irritation that his publisher has illustrated his history of Carthage with endless paintings of elephants!) in the darkest of all the I Claudius episodes.

Livila is desperate to marry Sejanus. He’s keen to do this, but is also agreeable when Tiberius suggests he marries Livila’s teenage daughter Helen (Karen Foley) instead. You can probably guess how Livila reacts to that (just wind Patricia Quinn up and let her go for several minutes).

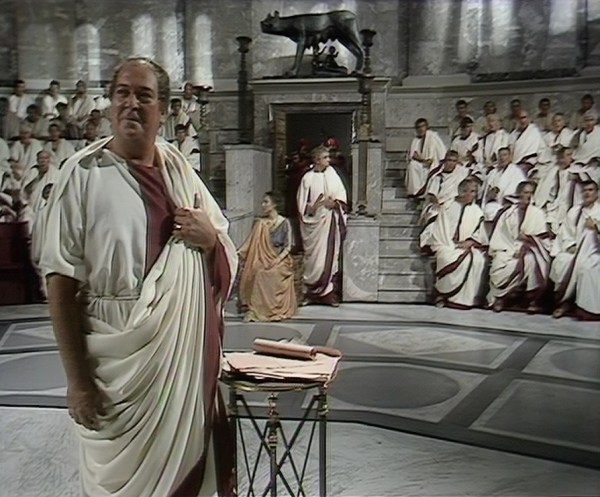

The corruption of Sejanus’ Rome is represented by the way one man dies – Gallus (Charles Kay). Gallus has three scenes – in the first he makes a principled stand in the Senate (earning Sejanus’ enmity) and in the second he shares a walk back to the Senate with Claudius (the pair have an amiable chat about history – his association with Claudius marking him out as a good guy).

His arrest and brutal torture demonstrates how Sejanus’ reign of terror operates – any opponent can be removed at any time and evidence simply isn’t required. There are so many fine cameo performances across the entire serial – Kay’s is just one among many. “I’ve watched your career with fascination, Sejanus. It’s been a revelation to me. I never fully realized before how a small mind, allied to unlimited ambition, and without scruple can destroy a country full of clever men”.

Antonia moves a little more to the forefront today. Her default expression is still disapproving (even now he’s middle-aged, Claudius can seemingly do nothing right in her eyes) but she does emerge as one of the few members of the Imperial family (along with Claudius, of course) who has a strong sense of morality. It’s remarkable that she’s remained innocent about so many things (the part her daughter Livilia played in the banishment of Postumus, for example) but this does seem to be genuine, rather than a politic avoidance of the truth.

So when she’s presented with evidence that Livila poisoned her husband Castor, she acts without hesitation. Locking her in a room and forcing herself to listen to Livila’s screams is a call-back to a similar scene with Augustus/Julia. But where Julia would eventually emerge (bound for exile) Antonia plans to keep vigil until Livila dies of starvation.

Claudius: How can you leave her to die?

Antonia: That’s her punishment.

Claudius: How can you sit out here and listen to her?

Antonia: And that’s mine.

While this is happening, Rome is in turmoil. Sejanus has been removed from power by his second in command Macro (John Rhys-Davies). Rhys-Davies is excellent value as the previously loyal Macro who now eyes a chance to advance. Caligula recommends him to Tiberius as a sound man (he doesn’t know him personally, but he’s slept with his wife several times!)

There’s a few rare handheld camera shots (the death of Sejanus, the aftermath of the massacre in the streets) that help to give the climax of the episode an unusual feel. The studio-bound nature of I Claudius means that it struggles to express a sense of scale (most of the turmoil has to take place off screen) but the visceral nature of the unfolding events still carries a considerable punch. The rape and murder of Sejanus’ young daughter is a case in point.

Reign of Terror is an exhausting episode. And the fact that Tiberius has named Caligula as his successor suggests that the next one will be no quieter …