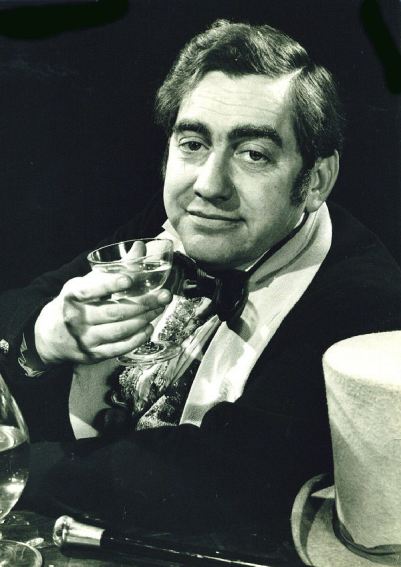

After languishing in obscurity for a fair few years, during the last week or so the name of Tony Hancock seemed to be everywhere. There’s been scores of newspaper features, a Newsnight discussion (which was ever so slightly toe-curling) as well as plenty of internet chatter.

And it’s all been about the new two hour documentary Very Nearly An Armful, premiered on GOLD yesterday (14th January 2023) as well as the transmission of two colourised episodes – one from Hancock’s Half Hour (Twelve Angry Men) and the other from Hancock (The Blood Donor).

To be fair, it’s probably the colourised episodes which have caught the imagination (I don’t recall the same furore of interest when GOLD debuted documentaries about the likes of Porridge, Only Fools & Horses or dinnerladies). Depending on where you stand, colourising Hancock is either a sacrilege or a sensible way to bring his material to a new audience reluctant to watch black and white material. I’ll turn my attention to the episodes later, but first the documentary ….

One of the problems facing any modern Hancock doco is the fact that virtually all of his friends and contemporaries are no longer with us. Earlier efforts (such as the peerless Heroes of Comedy – tx 2nd February 1998) featured substantial input from people who knew both the public and private Hancock (with their contributions supplemented by a handful of celebrity fans).

Now sadly, the reverse has to be the case. The majority of the talking heads in Very Nearly An Armful were recruited from the celeb ranks (plus a couple of members of the Tony Hancock Appreciation Society to provide more detailed background points). However, it was a pleasant surprise to find that two people who did know Tony – actress Nanette Newman and writer Richard Harris – were present.

Although neither made that great a contribution – especially Harris, since his association with Hancock (working on the short lived ATV series) was so brief – it was still more than welcome to have them as it helped to balance out the undoubted fannish love from the others.

Very Nearly An Armful had a mixed bag of contributors, but all seemed genuine in their love of the Lad (sometimes with shows of this type, you get the feeling that certain celebs – lured by a nice cheque – are quite happy to come along and speak about anyone, but that wasn’t the case here). Jack Dee was an ideal choice as host – like the others, his appreciation for Hancock shone through.

Even with two hours to play with, there were some surprising omissions. The radio incarnation of Hancock’s Half Hour (apart from – inevitably – Sunday Afternoon at Home) was glossed over very quickly which meant there was no time to discuss the contributions of Bill Kerr or Hattie Jacques. And out of Tony’s ‘rep’ of television actors, only Patricia Hayes merited a mention (Hugh Lloyd and John Le Mesurier could also have done with a spot of admiration).

There were plenty of well-chosen clips from Hancock’s Half Hour and Hancock (although surprisingly his debut television series – The Tony Hancock Show, written by Eric Sykes and transmitted on ITV – was omitted).

Since the documentary took a chronological approach, the second hour (Hancock’s decline and fall) was tough going at times. Partly this was because of the sadness of his spiral into alcoholism and failure (although Very Nearly An Armful only hints at how grim things really became) but it’s also fair to say that a two hour documentary, no matter how good, will always feel a little fatiguing for the viewer.

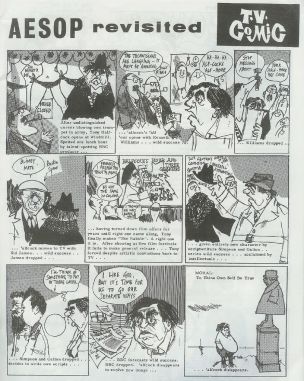

Points of interest in the second hour – a little love was shown for the ATV series, which was good to see. Alas, appreciation for The Punch & Judy Man was in very short supply, which did surprise me. Surely I can’t be the only one to enjoy it? There were also some snippets from his later ITV series which didn’t show the Lad at his best (wisely, no footage from the partly completed Australian series was used).

Although Very Nearly An Armful doesn’t shy away from Hancock’s difficult later years, it didn’t feel like a salacious investigation – which is a definite plus point. A slightly shorter edit might help to make it a better watch, but even in this form it’s a warm and affectionate tribute to a man who continues to inspire love and laughter today.

Prior to the broadcast of the colour Blood Donor, there was a short feature explaining how and why its come about. The most intriguing statement was from Kevin McNally, who said that Hancock’s programmes are slipping into obscurity because viewers no longer want to watch black and white material. Hmm …..

I think it’s more accurate to say that because stations like GOLD no longer air black and white programmes, the likes of Hancock’s Half Hour now have very few possible broadcasting outlets.

What makes McNally’s comment all the more surprising is the fact that Talking Pictures TV have been merrily broadcasting black and white television and films for a fair few years (earning many plaudits along the way). TPTV’s embrace of monochrome material and the enthusiasm of their audience for it rather destroys McNally’s argument I feel.

It’s possible to argue that younger people are more resistant to watching black and white programmes, but just how many young people would be tuned into GOLD on a Saturday evening? If you look at the limited range of GOLD’s programming (Only Fools & Horses, Porridge, Last of the Summer Wine, etc) then it’s difficult not to imagine that the average GOLD viewer is of a similar age to his or her TPTV counterpart. And if they can watch black and white programmes on TPTV, why not on GOLD?

An enormous amount of work went into the colourisation of these two episodes (click here) and you have to appreciate that, but I just find the whole thing rather pointless. In their colour state, the two episodes are perfectly watchable but I never felt I was looking at a genuine colour progamme (which rather defeats the object).

On the plus side, the episodes were restored prior to colourisation, so if you can turn the colour down (a tricky thing to do on a modern television) you’ll be able to see a definite improvement on the copies available on DVD.

The ironic thing is that few shows seem less suited to colour than Hancock’s Half Hour. The best of Hancock’s work takes place in a weary 1950’s post-war Britain that feels utilitarian and drab. Monochrome is ideal for this (as it would be for kitchen-sink dramas) so brightening everything up with artificial colour is an especially perverse move.

If GOLD do any more, or if they move onto other programmes like Steptoe & Son, then I won’t be watching as I’ll be quite happy to stick with my black and white originals. But if colourisation helps to open the shows up to a new audience (dubious though I think that is) then I can only wish them well.