Holmes muses to Watson that in his opinion “one of the most dangerous things in the world is the drifting and friendless woman. She may be perfectly harmless in herself, but all too often, she is a temptation to crime in others. She is a stray chicken in a world of foxes, and when she is gobbled up, she is hardly missed. I very much fear that some evil has befallen the Lady Frances Carfax.” This monologue is a preamble to Holmes’ request that Watson travels to the hotel in Lausanne (where Lady Frances was last seen) so he can investigate her sudden disappearance.

Holmes is convinced that the trip will do his friend good, since he’s observed that Watson has been feeling run-down lately. Watson, of course, is amazed that Holmes knows this – and Holmes’ explanation (involving the way Watson’s shoe-laces are tied) is a classic Conan-Doyle moment.

Watson travels to the hotel and speaks to the manager Moser (Roger Delgado). Moser mentions that Lady Frances seemed to be worried by a bearded stranger and there’s also the question of why she gave a cheque for fifty pounds to her former maid. The manager is also able to tell Watson that Lady Frances spent some time in the presence of Dr. Shlessinger and his wife. This seems to be a dead-end though, as Dr. Shlessinger is a man of piety and devotion who surely can have connection to the case.

Watson’s investigations continue, but it’s maybe no surprise to learn that all of his efforts turn out to be futile. Luckily, Holmes is on hand to shed some light on this tangled mystery.

The Disappearance of Lady Frances Carfax was originally published in 1911. Like the preceding story adapted for the series, The Retired Colourman, it’s memorable for depicting an independent Watson, sent off to investigate by Holmes. It’s just a pity that since this happened so rarely, the two were broadcast one after another.

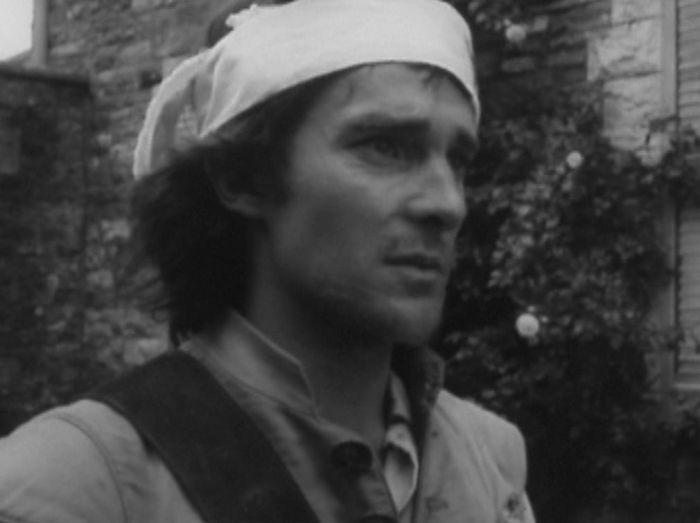

But no matter, as once again we can enjoy the sight of Nigel Stock’s Watson in investigative mode. As ever, Stock plays these scenes so nicely (witness the moment when Moser wonders if Watson is a detective and you can see Stock visibly grow in stature). Of course, things don’t go very well and he has to be rescued by Holmes after he gets into a tussle with the bearded stranger.

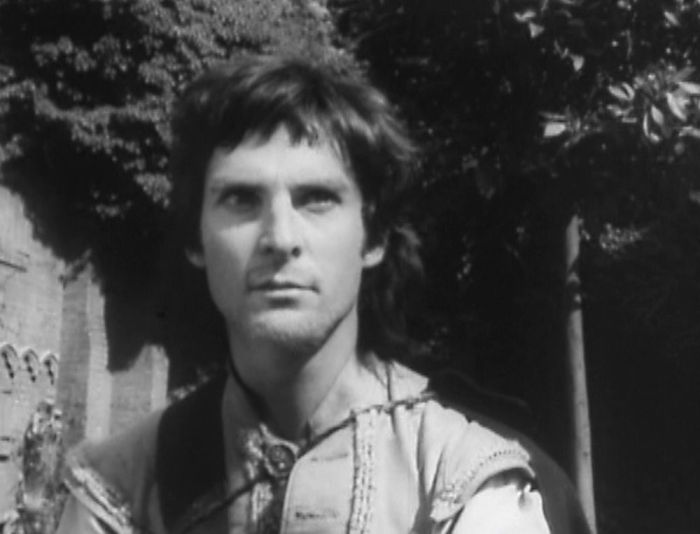

Despite Holmes’ claims that he was too busy to make the trip, he has (after reading Watson’s initial reports) decided to come over after all – and Wilmer’s sudden appearance is delightful. Holmes is wearing a very effective disguise and his ironic comment of “Dear me, Watson. You have managed to make a hash of things, haven’t you?” is one of the episode’s many highlights.

For those brought up with the efficient and unflappable Watsons of the Granada series, this may be a little difficult to take – but it’s totally consistent with Conan-Doyle’s original story. As good as the Granada series was (for the most part) it’s fair to say that on occasions, their eagerness to redress the perceived imbalance in some of the previous portrayals of Watson sometimes pushed the character too far the other way (making him rather too capable).

This excerpt from the Conan-Doyle story is interesting –

To Holmes I wrote showing how rapidly and surely I had got down to the roots of the matter. In reply I had a telegram asking for a description of Dr. Shlessinger’s left ear. Holmes’s ideas of humour are strange and occasionally offensive, so I took no notice of his ill-timed jest.

The clear inference from this is that Watson is heading for a fall, since we know that Holmes never makes a frivolous request. And the fact that Watson, after all his years of experience, should think so doesn’t reflect well on him.

It’s also worth viewing the Granada adaptation, which takes many liberties with the original story – including completely removing the plot-thread of Watson being sent to investigate Lady Frances’ disappeance (in the Granada version he’s already present at the hotel and sends for Holmes when he becomes concerned for Lady Francis’ safety). All of Watson’s mis-deductions are therefore absent, which isn’t surprising since they would have jarred with the efficient and capable picture of Watson presented since series one in 1984. It’s a valid decision, but it sits rather uneasily with the Granada’s original claim that they would return to the original stories and present them authentically (undoing the harm they considered was done by earlier portrayals, such as Nigel Bruce’s).

Thanks to Holmes’ intervention, it becomes clear that the bearded stranger is a friend not foe. His name is the Hon. Philip Green and had Lady Frances’ family not objected, he would have married her years ago. Joss Ackland (as Green) is completely unrecognisable (he’s sporting long black hair and a black beard).

One of my favourite actors, Ronald Radd plays Peters, the villian of the piece and a brief appearance by another favourite, Roger Delgado, is just the icing on the cake. Holmes and Watson return to London and track down Peters (the erstwhile Dr. Shlessinger). I love the moment when Holmes and Watson confront him. Holmes warns Peters that Watson is a very dangerous ruffian and, after a moments pause, Stock raises his stick in a mildly threatening manner! It’s only a little throwaway moment (possibly worked out in rehearsal) but it never fails to raise a smile.

Location filming in France helps to give the story a sense of authenticity and whilst there’s the odd production misstep (the body in the coffin looks very odd) all in all this is a very strong end to the series.

This would be Douglas Wilmer’s final appearance as Holmes in the series, as various factors made him decide not to return for a second run. These included problems with scripts, directors and the news that series two would be made to an even tighter production schedule than the first. For Wilmer (who considered that the quality of the series was already compromised) this was unacceptable, and it would be Peter Cushing who would have to deal with numerous production difficulties when the series returned in 1968.

It’s fair to say that the series suffers from the same problems of virtually every series of this era. Boom shadows are a regular presence and the sets sometimes wobble (and so do the actors!). The stories only had a limited amount of studio-time (with over-runs strictly frowned upon) so occasionally we will see scenes with technical problems (line-fluffs, malfunctioning props) that could have been resolved had the time been available for another take.

But the series also has all the strengths of television of this era – and the main strength is the sheer quality of the actors. Peter Wyngarde, Patrick Troughton, Patrick Wymark, Nyree Dawn Porter, James Bree, Anton Rodgers, Leonard Sachs, Derek Francis and Maurice Denham are just some of the fine actors to grace the stories prior to this one. And that’s not forgetting the numerous smaller roles which were equally well performed.

It’s not surprising that the lavish Granada series tends to be regarded as the definitive Sherlock Holmes television version as the BBC’s Sherlock Holmes will never be able to compete in a visual sense (the BBC series was much more studio-bound and therefore lacked the visual sweep of the Granada Holmes). But these adaptations were as good (and as faithful, if not more so) to Conan-Doyle’s original stories. Plus the first BBC series has an obvious trump card – Douglas Wilmer.

Few actors have ever been able to capture as well as Wilmer the icy, logical nature of Holmes. Watson once called him “the perfect reasoning machine” and it’s this precise, mechanical nature that Douglas Wilmer portrays to perfection. Many actors would have sought to soften him, but Wilmer stays true to Conan-Doyle’s original. It’s a performance that never fails to impress, as Wilmer (even in the scenes where he has little dialogue) is always doing something that’s worth watching.

He’s complimented by Nigel Stock’s Watson. It’s, at times, a rather comedic turn, but as I’ve mentioned it’s probably not as far removed from the original text as some people would think.

If you love Sherlock Holmes or you love 1960’s British television then the BFI DVD is a treasure.