Doomwatch ran for three series between 1970 – 1972. Like many programmes of this era, not all of the episodes now exist (out of 38 made, 14 are currently absent from the archives). Most of the wiped episodes come from the third and final series (five are missing from series one, whilst the second series exists complete).

Since only three episodes remain from the third series (including the untransmitted Sex and Violence) it’s always been hard to get a feel for how the last run developed. So this second edition of Deadly Dangerous Tomorrow (originally published in 2010) is very welcome as it contains five S3 scripts – Fire and Brimstone, High Mountain (both draft and camera scripts), Say Knife Fat Man, Deadly Dangerous Tomorrow and Flood. There’s also a S1 episode (Spectre at the Feast) and – new to this edition – a script by Keith Dewhurst that was submitted for the second series but rejected by series producer Terence Dudley.

The production history of Doomwatch is something of a battleground, due to (in the blue corner) Terence Dudley and (in the red corner) series creators Kit Pedler and Gerry Davis. Pedler and Davis, naturally enough, had very strong opinions about how their creation should develop, but Dudley was equally forthright and by the third series he had wrested complete control and was able to fashion the show entirely in his image.

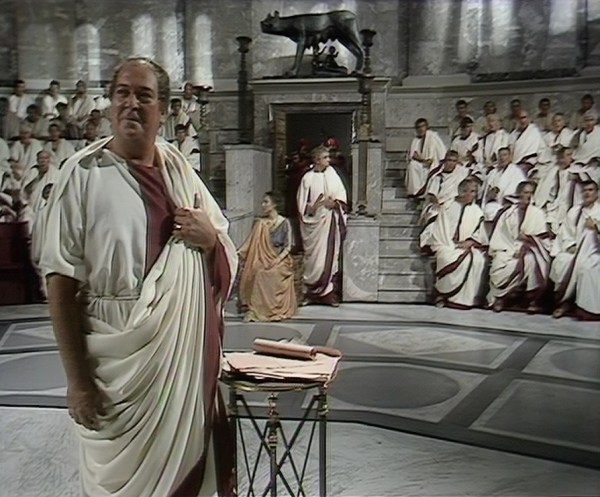

Dudley’s Spectre at the Feast is the first script in this book. It had a good guest cast (Richard Hurndall, William Lucas, George Pravda) so it’s possible to surmise we would have been on safe ground, acting wise, but how effective the overall production would have been (given some of the hallucinogenic sequences) is another matter.

The story reads well though, with Fielding (played by Lucas) coming across as the sort of strong opponent for Quist typical from this era of the programme. The reason for an outbreak of mass hallucinations (contaminated lobsters) is something you don’t see every day (it’s probably best if you suspend your disbelief when Quist proffers his explanation). John Ridge going undercover to a fancy hotel in order to steal a lobster from their tank is one reason why I really hope this episode turns up one day.

Remarkably (or sadly) so many Doomwatch episodes still seem relevant today – Spectre at the Feast (which pivots around the theme of river pollution) is no exception. Towards the end of the episode, Quist confronts Fielding.

Gentlemen, we have a lot to thank Mr Fielding for. He is pioneering in silicostyrenes. Soon, there will be no more cast-iron car engines – just cheap plastic cylinder blocks – and it won’t be one factory releasing effluent at the permitted level. Today he poisons the rich man’s lobster, tomorrow it’ll be the poor man’s fish and chips. He’s produced a cheaper engine. Do we want it at the price?

We then jump forward to the opening episode of series three – Fire and Brimstone. Another Dudley script, it heavily features John Ridge who, after stealing six deadly anthrax vials, attempts to hold the world’s governments to ransom.

Simon Oates (John Ridge) didn’t want to commit to the whole of series three (he would only appear in four episodes) so it’s understandable that Dudley would give Ridge a memorable lap of honour (he was hardly the sort of character to just meekly hand in his resignation). Doomwatch had already killed off a main character (Toby Wren) so possibly didn’t want to repeat that. Instead, John Ridge goes rogue in the most extreme way ….

By all accounts, this baffled and annoyed contemporary critics and viewers, who couldn’t understand why the previously affable (if highly strung) Ridge had suddenly become a fanatic – intent on wiping out millions of people if his demands aren’t met. An explanation – of sorts – is provided in 3.4 (Waiting for a Knighthood) the only existing John Ridge series three episode. Fire and Brimstone is an uncompromising and unsettling way to kick off S3, not least for the way it ends on the broken Ridge.

Two versions of Martin Worth’s High Mountain (episode 3.2) are included – firstly a draft script and then a re-written camera script. The main thrust of the plot remains the same, but the dangerous item under discussion – originally soap powder, later aerosol paint – changes as do some nips and tucks to the dialogue (which are always fascinating to pick up on).

A few lines swiftly dispose of two S2 regulars (Geoff Hardcastle, Dr Fay Chantry) who were deemed surplus to requirements by Terence Dudley. Neil Stafford (John Bown) now moves into view as Ridge’s replacement – albeit someone forced on Quist by the Minister to act as his eyes and ears (although Stafford quickly becomes a keen Doomwatch man).

Unlike the rather pallidly drawn Hardcastle and Chantry, there’s no doubt that Stafford makes his mark straight away (even more so in the draft script, where he dominates a subdued Quist). The notion of the Drummond Group offering Quist the money to set up a private Doomwatch, free from government interference, is an intriguing one (although inevitably strings are attached).

Next up (3.3) is another Martin Worth script – Say Knife Fat Man – which had quite the guest cast (Peter Halliday, Geoffrey Palmer, Leslie Schofield, Paul Seed, Elisabeth Sladen). The script is preceded by a letter from Worth to Terence Dudley, in which he wearingly describes how he had to undertake a hefty rewrite on the script.

Possibly this might explain why the story doesn’t quite grip. The main thrust of the episode (a group of disgruntled students steal some plutonium in order to make an atom bomb) – is decent enough, but both Quist and Stafford are rather passive throughout. It’s Chief Supt. Mallory (Geoffrey Palmer) who manages to put two and two together (indeed, it turns out to be a story where the Doomwatch team achieve very little). Possibly the most interesting part is the way that Barbara (by displaying sympathy for the alienated students) is allowed, for once, to be something more than just a line feed for the others.

There’s almost a Department S feel to the pre-credits sequence of Deadly Dangerous Tomorrow (3.7, written by Martin Worth). The mystery of how an Indian family – father, mother, children – dying of malaria and malnutrition end up in a tent pitched in Hyde Park is spun out for a little while.

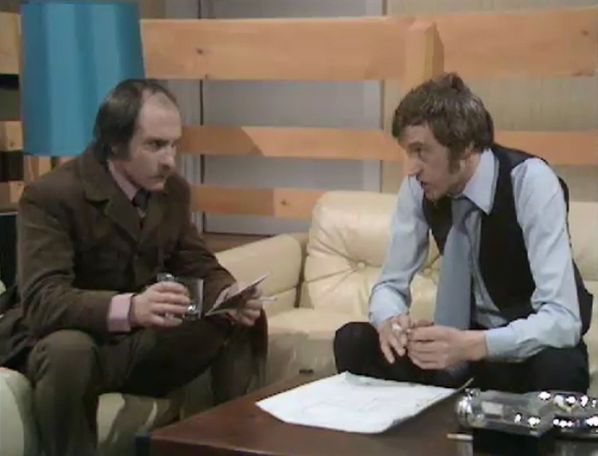

It turns out that John Ridge (no longer a member of Doomwatch, but equally no longer a menace to society) is partly responsible for bringing them to London. The suffering of the third world is his latest cause, although Stafford cynically suggests that Ridge is motivated by self interest. “So that’s why you took up the cause of the innocents and martyrs. Because you think you’re one yourself. That’s what it’s really about – poor, hard done by Ridge, whom nobody loves, getting his own back.”

Whatever the reason, the sudden appearance of Ridge in the new Doomwatch office mid way through the story gives the episode a considerable boost. The main guest character – Senator Connell – seems to be a little bit of a cliché figure but it would have been nice to see what Cec Linder (a familiar face from the television Quatermass and the Pit and the Bond movie Goldfinger) did with the role.

The last series three script included (3.9, written by Ian Curteis) is Flood. It has a tense feel throughout as abnormally high tides threaten to flood London, potentially affecting millions of people. Luckily, at the last minute the wind changes and the panic is over (which was probably just as well, as Doomwatch’s budget wouldn’t have stretched to depicting a flood-ravaged London).

The reason for the tides isn’t environmental – it’s due to secret nuclear tests which occurred on the seabed just a few hundred miles off the coast of Europe. This is the cue for Quist and the Minister to lock horns, although it’s noticeable that since he was first introduced, the Minister has become less of a pantomime villain and more of a three-dimensional character. He now possesses an agenda that isn’t simply designed to provide Quist with an adversary, instead it’s possible to appreciate (if not always sympathise) with the Minister’s point of view.

New to this edition is the snappily titled Home Made Bomb Story by Keith Dewhurst. Surprisingly, it isn’t actually about a home made bomb ….

Doctor David Daviot, an old pupil of Quist’s, is the central character. He’s a scientist with a conscience, but he comes across as rather boorish and unsympathetic (so it’s difficult to feel too invested about his fate). He does share some good scenes with Quist though and Quist is given a remarkably lengthy monologue about the death of his wife that could have been a stand out moment for John Paul (although one that probably would have been a pain to learn).

Home Made Bomb Story is certainly a curio (it’s jarring to hear Daviot refer to Quist as ‘Doc’) but given a few more drafts maybe it would have made the grade, but alas it wasn’t to be.

Deadly Dangerous Tomorrow is edited by Michael Seely, who knows his Doomwatch (you’re well advised to track down Prophets of Doom, an excellent production history of the series written by Seely and Phil Ware) not to mention archive television in general. He provides a concise introduction to set the scene, and supplies informative footnotes throughout. Some of the footnotes are production related (cut dialogue, etc) whilst others provide detail about the various environmental issues tackled in the stories.

This book is an excellent companion to the Doomwatch DVD, as it helps to flesh out the neglected third series. It’s also made me keen to revisit Doomwatch from the start, which is never a bad idea.

Deadly Dangerous Tomorrow comes warmly recommended and can be ordered via this link.