Robin and the others rescue a knight, who gives his name as Chevalier Deguise, from a band of Sherwood cutthroats. They treat him to a feast of meat and wine and then later politely request that he pays their bill. The knight has no money on him, but Robin notices that his horse is a fine beast and decides it would be a fair exchange for all the hospitality he’s received.

The knight challenges the outlaws to a wrestling contest – winner takes all – and Little John steps up to defend the honour of the Merry Men. But this is no light-hearted bout and the knight’s sheer power and will to win overcomes John. Shocked by what he’s seen, Robin asks him who he really is. The knight replies that he’s King Richard …..

With The King’s Fool, Richard Carpenter once again puts a twist on familiar aspects of the Robin Hood legend. Good King Richard (away fighting in the Holy Land or a prisoner in Germany) is a staple part of virtually every retelling of the tale. He’s generally presented as England’s one true hope, with his brother John painted as a venal usurper who lacks all of Richard’s fine qualities.

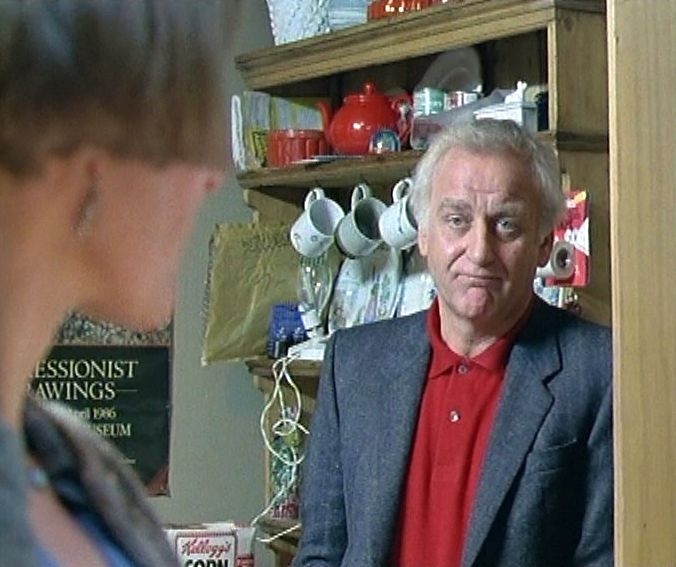

As the opening credits tell us that John Rhys-Davies is playing King Richard, the audience is placed in the position of knowing more than Robin and the Merry Men right from the start (which gives the opening fifteen minutes a little extra frisson). For example, when Robin passes around the communal bowl with the ritual words “Herne protect us” Richard prefers instead to honour “King Richard”. The others, after a momentary pause, nod in agreement.

But although they don’t dismiss Richard out of hand, it’s also plain that most of them share no particular love for their King. Most outspoken is Will, who regards him as just another lord and master (and just as corrupt). Ray Winstone pulses with anger in this scene as does Rhys-Davies (who, remember, has yet to reveal his true identity). It look as if Richard and Will might come to blows, but Robin manages to diffuse the situation. However, the irony that the hot-headed Will is completely right from the beginning is clearly not accidental ….

The wrestling match is brutal, with both Richard and Little John almost reverting to an animalistic state. After Richard emerges victorious and reveals himself to be their King, he pardons Robin and the others. They might be outlaws, but they saved his life and that – in his eyes – wipes the slate clean.

Robin is keen to go to Nottingham to attend Richard, as are the others, all except Will. “I trust very few people, and I’m looking at all of ’em. I’d die for each one of you. But there’s no way I’m going to Nottingham”. Perceptively he casts doubt on the permanence of Richard’s patronage. He’s pardoned them now, but what happens tomorrow or the day after? That Will’s the only one to realise this is a slight weakness of the story – as the others calmly walk into Nottingham and allow themselves to be apprehended by Gisburne and presented to the King in chains.

The predictable happens – Richard angrily tells Gisburne to release them and Robin and the others are treated as honoured guests – but it would have probably served them right if Richard had decided to have them all executed on the spot. Presumably Robin’s still dazzled by Richard’s star-power (the moment where the King offers Robin his hand to kiss in the forest is a nicely played scene by Michael Praed – watch how Robin flinches before accepting the honour). For those brought up on the previous Robin Hood stories which presented Richard as the “hero”, everything seems to be moving in the direction you’d expect. This Richard might be louder and more boorish than most versions of the King, but he’s pardoned Robin so he must be good, mustn’t he?

The first discordant note is struck when Robin attempts to make an appeal to Richard on behalf of the poor. The King, only half-listening, cuts him off mid-way through and whilst he applauds Robin’s sentiments it’s plain that this is done only for show. The King is a skilled politician and by co-opting Robin he’s removed a potentially dangerous enemy and turned him into an ally.

Robin remains flattered for a while that his opinions are sought (to the obvious irritation of the Sheriff) but his desire to serve the King only helps to speed up the fractures in the Merry Men. Will was the first, but now – one by one – they leave him, until only Tuck, Marion and Much are left. Almost too late Robin realises he’s been well and truly manipulated – Richard has no love for either England or its people. Little John succinctly sums up their feelings. “I loved you, Robin. You were the Hooded Man, Herne’s Son, the people’s hope. Now … now you’re the king’s fool.” Mantle, his eyes full of tears, plays the scene well.

The King, having tired of Robin, decides that the Hooded Man should die and Gisburne is despatched to do the deed. The action ramps up after Gisburne takes a shotbow bolt in the back (fired by Marion) and Robin faces stiff opposition from a number of sword-wielding soldiers.

Marion’s been fatally wounded and only the magic of Herne can save her. Following Robin Hood and the Sorcerer, the mystical elements of the series have rather taken a back seat (although The Witch of Elsdon did have some handy prophecies which moved the plot along nicely). The miraculous revival of Marion does feel like a little bit of a cheat, since it begs the question why Robin doesn’t call on Herne every time somebody’s close to death

But although it’s a little irksome in story terms, it’s still an impressively shot and acted sequence as Robin and Marion end up at the same stone circle seen at the start of the series (the one where his father was killed by the Sheriff’s men fifteen years previously). And as if by magic the Merry Men reappear. Now that Robin has rejected the illusionary power offered by the King they’re all free to take up residence in Sherwood once more.

Thanks to a pulsating performance by John Rhys-Davies, The King’s Fool closes series one on a high. Apart from maybe a slight dip with The Witch of Elsdon, the quality remained very consistent and series two would maintain – and at times better – this high standard.