Gerald Flood, what a trooper! He spends the first few minutes of Zero Hour on the Red Planet doing his very best to convince the audience that he’s being attacked by Martian lichen. Alas, it’s painfully obvious that the lichen is plastic and inanimate, which requires Flood to wriggle about frantically in order to sell the illusion that the plants are moving. It’s not at all convincing, but you have to give him top marks for effort.

As for the others, Brown reveals that the life he’s observed is plant-life. After four episodes of his imaginative world building, it’s something of a disappointment that we haven’t met the thriving Martian civilisation he promised us. This highlights the way that the Pathfinders series to date has trod a delicate line between science fiction (a twelve year-old girl with no space experience wants to become an astronaut? No problem!) and science fact (throughout the serial Brown has been the only one to believe that there could be intelligent life on Mars, with the others – even the children – adamant that only plant life could exist).

I did fleetingly think that a Martian was going to make an appearance at 6:41 during this episode, but it was only a guest appearance from a camera! It quickly bobs out of shot in a rather apologetic way.

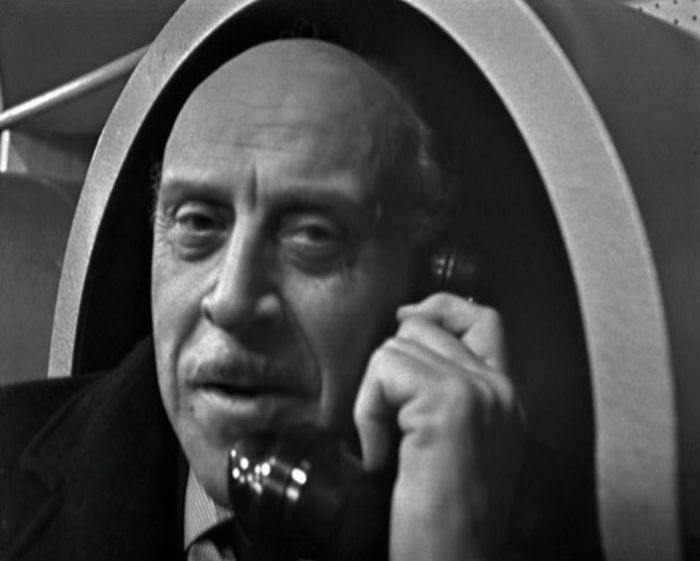

Stewart Guidotti demonstrates that Geoffrey’s concerned about the fate of Henderson and Mary by shouting an awful lot. It’s very much a performance that’s lacking in subtlety (to put it mildly) and with Hester Cameron emoting in a similar way, the pair of them are rather trying. Thank goodness for George Coulouris. Harcourt Brown may have been forced to accept that his vision of a Martian civilisation is now looking very unlikely, but he chooses to underplay, rather than overplay, his scenes.

Brown, Margaret and Geoffrey set off to look for Henderson and Mary. The pair have little oxygen and are being menaced by approaching lichen. Normally you’d have expected Henderson to have given Mary a comforting kiss by now, but since they’re wearing space helmets it’s not possible (the clash of heads would probably be rather painful). It slightly stretches credibility that within a few minutes they’re all reunited – although there’s a problem (Henderson and Mary are standing on the other edge of a crevice).

Cue several minutes of Brown and the children turning their supply sled into a bridge. Mary makes her way across (Pamela Barney doing her best to convince the audience that if Mary fell she’d plummet hundreds of feet) and Henderson follows. Hmm, for no good reason he decides to walk across agonisingly slowly – so you can guess what’s going to happen next. The bridge collapses and he ends up clinging to the edge of the crevice for dear life. It’s another of those moments that’s problematic, which is down to the limitations not only of the studio but also the fact they were recording “as live”. A few more takes and tighter editing would have sold the illusion much better. This moment of jeopardy is short-lived as the others easily pull him up.

Whereas Pathfinders in Space was a rather thoughtful sci-fi parable (the story of how an advanced civilisation was destroyed by war) Pathfinders to Mars has tended to eschew that path and has gone instead for pulp thrills. We’ve had the aggressive lichen, Henderson clinging on to the edge of a crevice for dear life and now Mary tumbles into Martian quicksand, with Henderson risking his life to save her. And even though this serial was an episode shorter than the previous one, these moments of jeopardy feel very much like padding – they’ve run around the Martian surface for twenty five minutes but have achieved very little.

Zero Hour on the Red Planet does have a cracking cliffhanger though – Brown elects to leave the others behind and pilot the rocket back to Earth by himself. He can’t bear the thought that they would expose his vision of Mars as a sham – so he’s prepared to leave them all (even the children) behind to die. But as he prepares to lift off, lichen forces itself into the control room …..