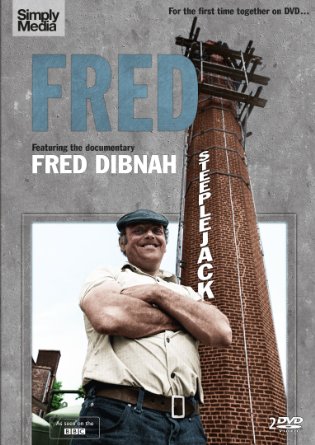

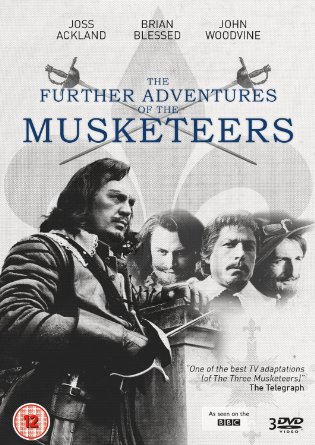

Broadcast between May and September 1967, The Further Adventures of the Musketeers (based on Dumas’ novel Twenty Years After) was a sixteen-part serial which followed on from the previous years adaptation of The Three Musketeers.

Brian Blessed and Jeremy Young returned as Porthos and Athos, but there were also two important changes. Joss Ackland took over the role of d’Artagnan from Jeremy Brett whilst John Woodvine replaced Gary Watson as Aramis.

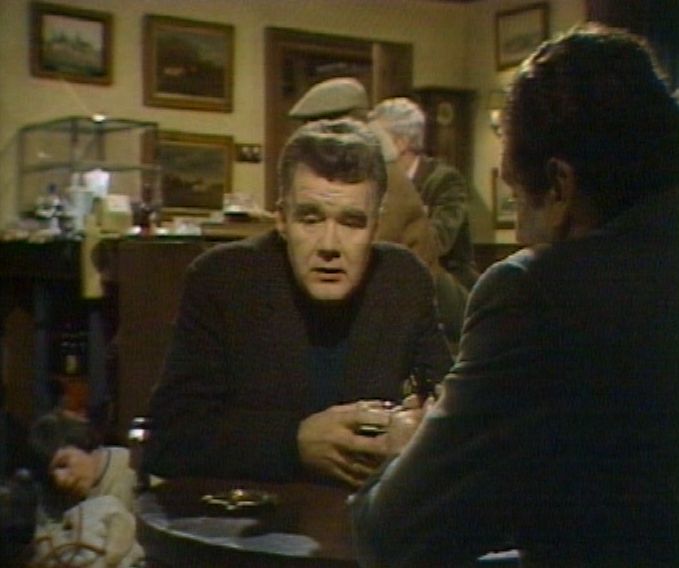

I have to confess at not being terribly impressed with Brett’s performance as d’Artagnan, so I wasn’t too sorry he didn’t return – although it would have been intriguing to see how he would have handled the older, more cynical character seen in this story. In The Three Musketeers, d’Artagnan is young, keen and filled with dreams of heroism. It’s therefore more than a little jarring when Ackland’s d’Artagnan is introduced at the start of the first episode.

Others may continue to call him a hero, but he’s not convinced. Although he still holds a commission in the Musketeers, it now appears to be a hollow honour – especially since his three former steadfast friends (Porthos, Aramis and Athos) have all left and gone their separate ways. When he recalls their old battle cry (“one for all, and all for one”) it’s done so ironically and whilst he bursts onto the screen with an impressive bout of swordplay, it was only to subdue a drunk in a tavern. Brawling in taverns seems to be something of a comedown for the brave d’Artagnan, as he himself admits.

He’s therefore keen to grasp any opportunity to rekindle the glory days of old and when Queen Anne (Carole Potter) asks for his help, how can he refuse? Potter was something of a weak link during The Three Musketeers and her rather grating performance continues here. This may be a deliberate acting choice though, as we see over the course of the serial that the Queen is a far from admirable character – instead she’s capricious, vain and frequently misguided.

d’Artagnan pledges his allegiance to the Queen, her young son, King Louis XIV (Louis Selwyn) and Cardinal Mazarin (William Dexter). They are the orthodox ruling establishment, but the majority of the people seem to side with the imprisoned Prince de Beaufort (John Quentin).

The question of personal morality is key, especially when understanding which side the four Musketeers support. As we’ve seen, d’Artagnan supports the Cardinal and Queen, but is this because he believes they are the right choice for France or is it just that they’ve offered him a chance to redeem his tarnished honour?

When d’Artagnan meets up with Porthos, his former colleague quickly joins him. Blessed, a joy to watch throughout the serial, is never better than in his first scene. He’s the lonely lord of a manor, complaining that his neighbours consider him to be something of a peasant and won’t talk to him, even after he’s killed several of them! So he agrees to join d’Artagnan, mainly it seems because he’s always keen for a scrap.

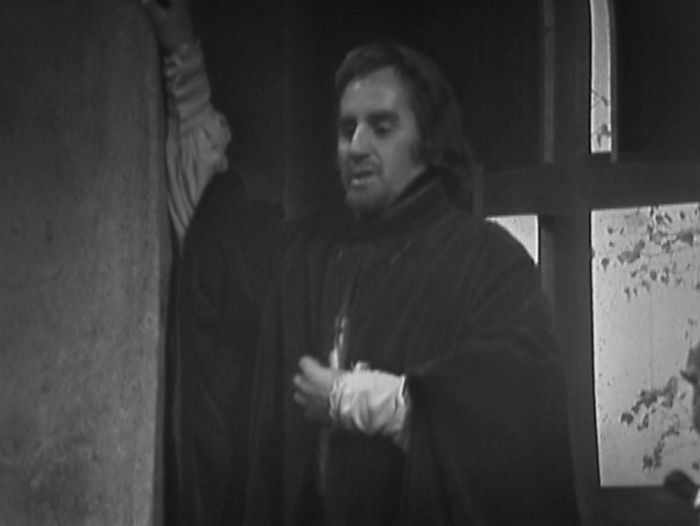

But Aramis and Athos are both on the Prince’s side. They believe their cause is just and Athos regards d’Artagnan’s allegiance to the Cardinal with extreme disfavour. Athos supports the King, but in his opinion the Cardinal is manipulating both the King and the Queen to serve his own ends. It’s telling that d’Artagnan doesn’t deny this.

Joss Ackland, from his first appearance, is totally commanding as d’Artagnan. If Brett’s take on the role tended to see him play the character at a hysterical pitch then Ackland is much more restrained and therefore much better. As I’ve said, Brian Blessed is tremendous fun – he gets to shout a lot and has some great comic lines. John Woodvine, a favourite actor of mine, is excellent as Aramis whilst Jeremy Young once again impresses hugely as Athos.

Although there wasn’t a great deal of evidence of this in The Three Musketeers, at the start of this serial d’Artagnan tells us that Athos was always his mentor and closest friend (essentially a second father to him) so the fact they are on opposing sides means there’s some dramatic scenes between them.

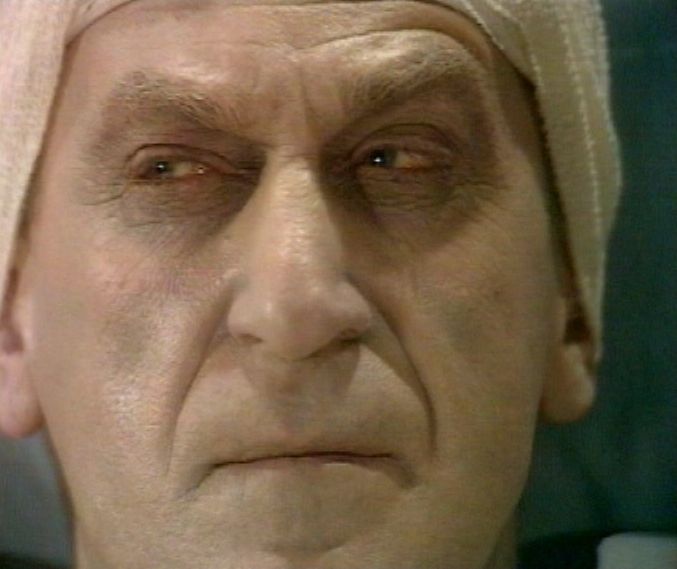

Young, a rather underrated actor I feel, is compelling across the duration of the serial. Athos’ monologue in episode five, after d’Artagnan bitterly rounds on his old friends, is one performance highlight amongst many. “We lived together. Loved, hated, shared and mingled our blood. Yet there is an even greater bond between us, that of crime. We four, all of us, judged, condemned and executed a human being whom we had no right to remove from this world. What can Mazarin be to us? We are brothers. Brothers, in life and death.”

Athos is referring to the murder of his former wife, Milady de Winter. As we’ve seen, her death still preys heavily on his mind – but he’s not the only one. She had a son, Mordaunt, who spends the early episodes vowing vengeance on the men who murdered his mother. As the serial progresses we see that his thirst for revenge makes him a formidable foe. A variety of other plot threads also run at the same time – such as the kidnapping of the boy King, Athos and Aramis’ secret mission to England to rescue King Charles I (d’Artagnan and Porthos are also in England and change sides to fight for the King) and the continuing conflict between Queen Anne and Prince de Beaufort – all of which helps to ensure that the story, even though it lasts sixteen episodes, never feels repetitious.

Plenty of quality actors drift in and out. Edward Brayshaw (once again resplendent in a blonde wig and complete with a wicked-looking dueling scar) returns as Rochefort, Michael Gothard is suitably villainous as Mordaunt, Geoffrey Palmer is memorable during his fairly brief appearance as Oliver Cromwell, David Garth is remote and aloof as King Charles I, whilst the devotee of this era of television can have fun picking out other familiar faces such as Nigel Lambert, Anna Barry, Morris Perry, Vernon Dobtcheff, David Garfield and Wendy Williams.

The budget was obviously quite decent, as there’s a generous helping of location filming and several notable set-pieces – such as the Prince’s escape from his prison fortress, which sees him absail to safety from the castle ramparts (although the use of illustrations as establishing shots for various locations is never convincing). Generally though, Stuart Walker’s production design is impressive – for example, his studio reproduction of Notre Dame Cathedral includes various architectural features from the original. Few would have missed them had they not been there, but it’s a nice example of the trouble taken to be as accurate as possible.

With a number of interconnecting plotlines, there’s certainly a great deal to enjoy in Alexander Barron’s dramatisation. The episodes set in England may lack a little tension (as we know Charles is doomed to die) but his execution is still a powerful moment. Athos is under the scaffold, frantically attempting to rescue the King, and is crushed when he realises that all his efforts have come to nothing. A macabre note is created when Charles’ blood drips through the floorboards onto the numb Athos. Christopher Barry and Hugh David share the directorial duties and although there’s (possibly thankfully) few of the directorial flourishes that made The Three Musketeers notable, they manage to keep things ticking along nicely.

The Further Adventures of the Musketeers looks and sounds exactly how you’d expect an unrestored telerecording of this period to look and sound. It’s perfectly watchable, although the picture is a little grainy and indistinct at times (and the soundtrack can also be somewhat hissy). A full restoration would have been possible, but as always it’s a question of cost. Niche titles like this don’t sell in huge numbers, so it’s no surprise that this DVD was a straight transfer of the available materials.

But although the picture quality is a little variable, the story and the performances of the four leads more than makes up for it. With many classic BBC black and white serials still languishing in the vaults, hopefully sales of this title will encourage more to be licenced in the future.

The Further Adventures of the Musketeers runs for sixteen 25 minute episodes across three DVDs. It’s released on the 23rd of May 2016 by Simply Media with an RRP of £29.99.