The stories of Robin Hood have proven to be evergreen and have featured in numerous film and television adaptations over the years. On British television, probably the two best-remembered takes on the character are Richard Greene’s The Adventures of Robin Hood (1955-1960) and Richard Carpenter’s much later, somewhat radical reworking of the legend, as seen in Robin of Sherwood (1984-1986).

The Legend of Robin Hood, broadcast in 1975, was a six-part serial which drew some of its inspiration from the earliest surviving written material (namely the ballads, such as A Lytell Geste of Robyn Hode). Naturally, some elements (such as Robin’s beheading of the Sherrif) are omitted and The Legend of Robin Hood is also content to cherry-pick material from later interpretations of the stories (neither Maid Marion or King Richard appear in the ballads, for example).

One of the strengths of The Legend of Robin Hood is that it’s a serial, rather than a series, so the tale it tells is finite – with a beginning, a middle and an end. As enjoyable as the Richard Greene series was, it did have a seemingly endless number of episodes, which ensured that character development could never be anything other than minimal. Although Robin of Sherwood was also a series, the decision by Michael Praed to jump ship (for the dubious pleasures of Dynasty) after series two did mean that his character (Robin of Locksley) could have a clearly defined fate, something also shared by Martin Potter’s Robin.

After serving a decent apprenticeship in numerous films and television series, The Legend of Robin Hood seemed to be Potter’s first step towards a more substantial career. But for whatever reason this never happened and his credits eventually spluttered to a halt – after an episode of All Creatures Great and Small in 1988 there’s nothing until the rather undistinguished television movie The Outsiders in 2006. But although his later career never developed in the way I’m sure he would have wanted, he still makes a first-class Robin Hood.

He’s supported by an impressive roster of acting talent – Diane Keen as Maid Marion, Paul Darrow as the Sheriff of Nottingham, William Marlowe as Sir Guy of Gisborne, John Abineri (later to take a key role in Robin of Sherwood) as Sir Kenneth Neston, David Dixon as Prince John, Tony Caunter as Friar Tuck, Conrad Asquith as Little John, Michael J. Jackson as King Richard and Yvonne Mitchell as Queen Eleanor.

Part one opens with the Earl of Huntingdon (Anthony Garner) preparing to leave for France. Before he goes, he places his infant son, Robin, in the charge of Father Ambrose (David King). Ambrose is charged to find the young Robin a safe place to live and when he’s of age he’ll be told that he’s the rightful heir to the Huntingdon estates. In some versions of the Robin Hood legend he’s a lowly-born Saxon and in others he’s the noble Earl of Huntington, so it’s a nice twist that this adaptation is able to incorporate both.

Robin is brought up by the forrester John Hood (Trevor Griffiths) and remains ignorant of his true identity. This isn’t the most effective part of the story as it’s hard to understand why the young Robin would have been removed from the manor at Huntingdon – surely his father could have found somebody he trusted to act as guardian in his absence? It also has to be said that Robin takes the news that he’s the Earl of Huntingdon very calmly (Martin Potter registering no more emotion than if he’d just been told it was raining outside). But now the truth is known he sets off to London to seek an audience with King Richard and claim his inheritance.

He’s somewhat delayed, as on the way he meets Lady Marion and her uncle, Sir Kenneth Neston. Neston, like Robin, is a proud Saxon, so Robin is perturbed to discover that he plans to marry his niece to Sir Guy of Gisborne. Earlier, Robin saw an example of Sir Guy’s brutal justice (a man arrested for stealing berries from one of Sir Guy’s bushes) so he queries why. Neston believes that marriages between Saxons and Normans will dilute the Norman influence – Robin is polite, but noncommittal.

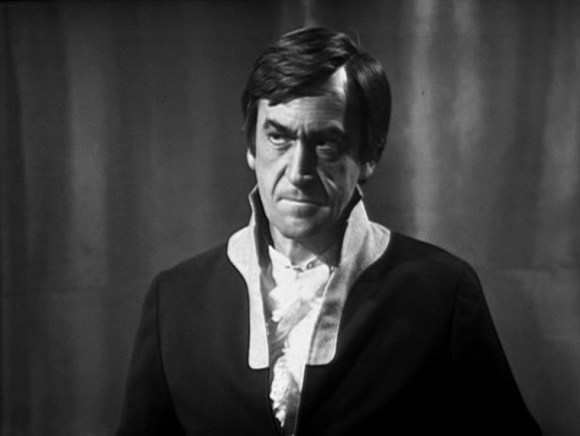

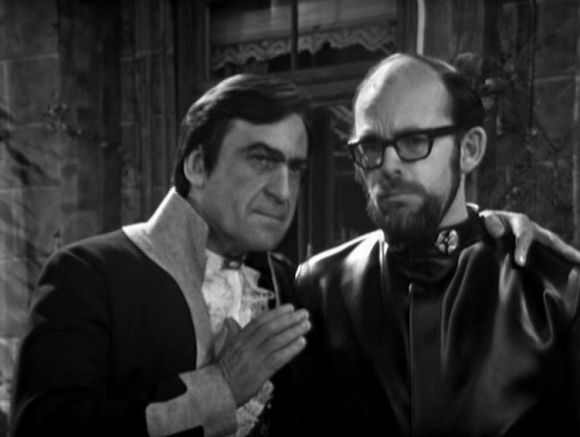

William Marlowe always offered a nice line in dangerous villains and his Sir Guy is no different. Although Sir Guy is polite and courteous in this episode (and also seems sincere in his love for Marion) Marlowe manages to give the impression that he could erupt into violence at any moment. He dominates the first scene with the Sheriff of Nottingham and the Abbot of Grantham (David Ryall) although a later scene between the Sherriff and the Abbot gives a chance for Paul Darrow to show that he can be equally as dangerous.

There’s no doubt that the DVD picked up some sales due to Darrow’s appearance. Thanks to his always watchable performance as Avon in Blakes 7, he’s maintained a healthy fan following. Whilst he resists the temptation (unlike some of the later Sheriffs) to go way over the top, his Sheriff does have flashes of cold violence, which are rather Avon-like.

Diane Keen is a winsome and appealing Maid Marion. It’s a more traditional performance than some of the later, more warrior-like, versions. This Marion, whilst she has a mind of her own, is presented as a heroine to be saved (screaming and almost insensible when attacked by a gang of outlaws, for example).

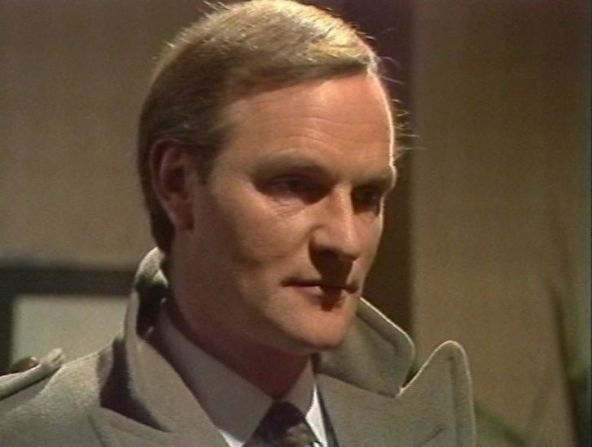

Michael J. Jackson may lack the imposing presence of some other notable Richards, such as Julian Glover or John Rhys-Davies, but despite his rather slight frame he’s still commanding. He easily manages to best his brother John, who pleads with him to be made regent before Richard departs for the Holy Land. David Dixon (later to be the unearthly Ford Prefect in the BBC1 adaptation of The Hitch-Hiker’s Guide to the Galaxy) offers a similarly off-kilter performance here. Although he has only a few moments screen time in part one, Dixon still makes an impact as John comes over as a spoilt, weak and unstable man who is easily manipulated.

Many adaptations of the Robin Hood stories open with Richard already in the Holy Land. This one is a little different, as we see Richard preparing to leave (with Robin due to join him). Richard has recognised Robin as the rightful heir to the Huntingdon estates and he bestows further honour on him by making him his squire. The outspoken Robin isn’t pleased though as he believes that strife will befall the kingdom if the King leaves to fight the Saracens.

Although Robin’s not yet an outlaw (and we’ve yet to meet the Merry Men) quite a lot of ground has been captured in this first episode. Production wise, it’s typical of the era (interiors shot on VT and exteriors on film). For anybody used to programmes from this era, the production values are pretty typical (although it must be said that some of the interior sets do look uncomfortably stagey). Possibly the worst production flaw comes at 45:54, when the edge of the backcloth (which has been hung to simulate evening outside the windows of the Throne Room) is clearly visible.

Martin Potter is an earnest and likeable Robin Hood, although it’s true that he does sound rather well spoken for somebody brought up in humble surroundings. But whilst he lacks the impish humour of some of the other Robins, he still comes over as a likeable leading man and the first fifty minutes have laid the ground nicely for the remainder of the serial.

Paul Darrow & David Ryall

William Marlowe

David Dixon

Diane Keen

John Abineri

Martin Potter

William Marlowe, David Ryall and Paul Darrow

Michael J. Jackson

Paul Darrow