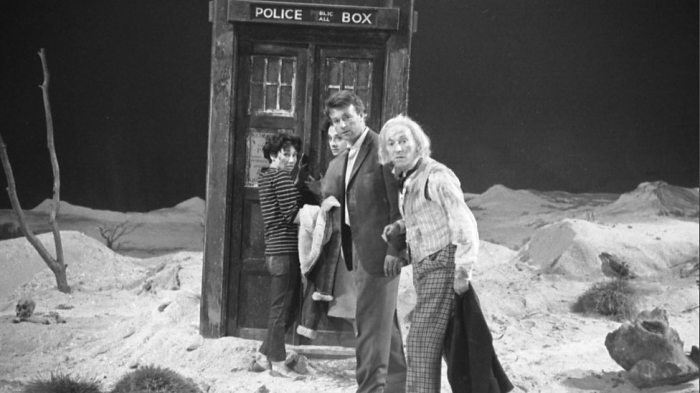

This is odd. A mysterious explosion in the TARDIS has robbed everybody of the ability to act. William Hartnell’s the luckiest, as he spends the first ten minutes unconscious on the floor whilst Jacqueline Hill doesn’t come off too badly (she’s been positioned as the sensible one since the first episode and that carries on here).

It’s William Russell and Carole Ann Ford who get the rough end of the stick. Whether it was as scripted or Russell’s choice, but for the first half of the episode Ian’s lines are spoken in a numbing monotone whilst Ford enjoys violent mood swings as Susan goes somewhat loopy.

There’s a number of bizarre moments, but one of my favourites is at 7:21 when Susan tries the controls of the TARDIS and extravagantly plummets to the floor. “She’s fainted” says Ian afterwards, blindingly stating the obvious.

This was the first story to use stock music rather than specially composed tracks. Eric Siday was the composer and one of the cues should be familiar (as it was later reused in The Moonbase). But the problem is that there’s not enough music and ambient sound effects used – meaning that for long stretches there’s nothing but the raw studio sound.

A prime example is when Susan comes back into the console room and notices that the TARDIS doors are open. This is clearly a dramatic moment – the ship hasn’t landed so it shouldn’t happen – but it’s played out to a totally dead atmosphere – no music, no effects. It’s possible that this was intentional (to highlight something was wrong with the TARDIS). Or possibly not. It all depends how generous you want to be, I guess.

After fainting, Susan threatens Ian and later stabs her bed with a pair of scissors in a notorious scene which was somewhat controversial at the time. Why Susan is acting irrationally (and why Ian doesn’t seem to be acting at all!) is never made clear – was this due to the explosion at the start or is it part of the TARDIS’ defence mechanisms (which we’ll discuss during the next episode).

This is an interesting exchange –

SUSAN: I never noticed the shadows before. It’s so silent in the ship.

BARBARA: Yes. Or we’re imagining things. We must be. I mean, how would anything get into the ship, anyway?

SUSAN: The doors were open.

BARBARA: Yes, but, but where would it hide?

SUSAN: In one of us.

It’s a red herring as nothing did get into the ship, but the concept that an alien invader might be hiding in one of them is a powerful and disturbing one.

The Doctor’s now up and about and is convinced that Ian and Barbara have sabotaged the TARDIS. It’s not possible to say for certain that the Doctor is acting irrationally (like Susan) because he’s been a very changeable character since episode one.

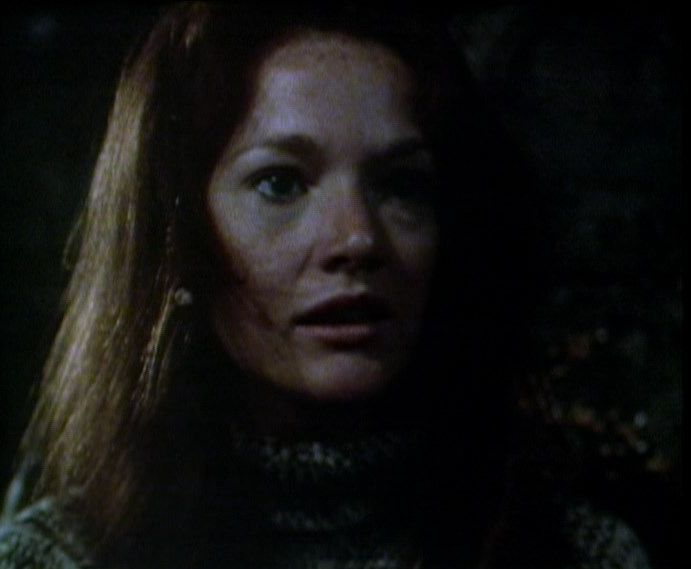

I think it was simply the Doctor being his usual suspicious, arrogant self – but it gives Barbara the chance to tell him some well deserved home truths. Jacqueline Hill is wonderful in this scene, as she is throughout the episode. Whilst the others have been erratic, Barbara remains strong.

BARBARA: How dare you! Do you realise, you stupid old man, that you’d have died in the Cave of Skulls if Ian hadn’t made fire for you?

DOCTOR: Oh, I.

BARBARA: And what about what we went through against the Daleks? Not just for us, but for you and Susan too. And all because you tricked us into going down to the city.

DOCTOR: But I, I.

BARBARA: Accuse us? You ought to go down on your hands and knees and thank us. But gratitude’s the last thing you’ll ever have, or any sort of common sense either.

Frankly it’s worth sitting through the episode for that exchange alone.

We end with the Doctor having drugged(!) the others so he can examine the TARDIS in peace. But somebody then attacks him. Or do they? Possibly it’s just a very contrived cliffhanger. All will be revealed when we reach The Brink of Disaster.