Rumours of Death

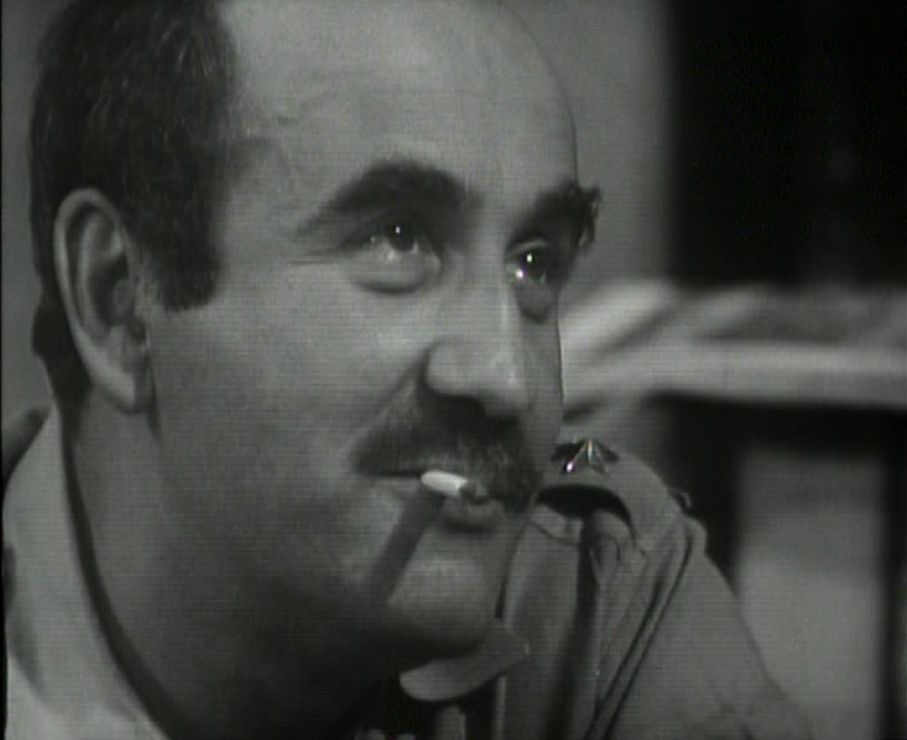

I love the cold opening – a pity that the show didn’t do more of this. Unshaven and in pain, we share Avon’s disorientation as he’s visited in his cell by Shrinker (John Bryans). The prison cell is a simple set, but off-camera screams from other, less fortunate, inmates helps to create a sense both of scale and oppression. Fiona Cumming’s direction here, and throughout the episode, has some nice choices – with Shrinker standing and Avon sitting, the low camera angle reinforces the Federation man’s dominance (at least initially).

Avon’s ruthlessness is perfectly demonstrated in this episode (as well as his single-minded desire to withstand anything – even days of torture – to achieve his ultimate goal). Whether this is a good or bad thing is debatable – it’s easy to argue that the seeds of his eventual downfall were sown here. After killing the most important woman in his life (who betrayed him) it surely would make killing the most important man in his life (whom he believed had betrayed him) much easier.

After some of the more pulpy sci-fi stories of series three, Rumours of Death is a pleasingly straightforward thriller/spy yarn. And whilst the palace revolution – and Servalan’s temporary dethroning – was achieved rather easily, this could be taken as an illustration of just how tenuous her grip on power was at this point.

Jacqueline Pearce doesn’t have a great of screentime, but her scenes with Avon are pulsating (especially “It’s an old wall, Avon, it waits. I hope you don’t die before you reach it.”). Although once again it’s remarkable that Avon and Servalan keep on running into each other when they’ve the whole galaxy to play with.

Greenlee (Donald Douglas) and Forres (David Haig) are a couple of interesting characters – Federation types who also seem like fairly ordinary people. The fact they’re a likeable double-act helps to blur the lines between the “good” and “bad” sides. Sula (Lorna Helibron) is another example of this – is she a pure rebel, keen to restore democracy with a People’s Council, or does she just have her eye on replacing Servalan?

The revelation that Sula was Anna (and therefore everything Avon thought he knew was wrong) means that he has – in his own mind – no choice but to kill her. Whether she did really love him (as her dying words suggest) is another of those moments that’s open to interpretation. And that’s one of the reasons why Rumours of Death is such a good episode – few B7’s have this level of nuance. Who do you trust and who do you disbelieve?

Although the episode Blake wasn’t even a gleam in Chris Boucher’s eye when he scripted this one, in retrospect it’s easy to see how even at this point Avon was firmly set on the road to Gauda Prime.

Sarcophagus

You can’t help but love and respect a story which begins in such an oblique and bewildering fashion. Sarcophagus‘ first five minutes pass by with no explanation, although the roles of the masked servitors will become clearer later on (when we see the Liberator crew occupying the same positions).

As with most of S3, there’s a definite feeling of ennui hanging over the crew. With no particular goal in sight, they spend their time doing relatively little (you know things are desperate when Vila and Avon are indulging in a game of space draughts). Tarrant’s asteroid (“something else to chase” as Cally says) is the latest example of a mission which seems to be designed more to keep them busy, than for any other pressing reason.

Largely set aboard the Liberator and (apart from some non-speaking extras) solely centered around the regulars, Sarcophagus may have been designed as a cheap show, but Tanith Lee was able to work with these limitations and unlike, say Breakdown (another Liberator heavy story), ensure that everybody was well served by the script. Avon and Cally top and tail the story (with other intriguing scenes scattered throughout), Tarrant might be his usual annoying self when interrogating Cally early on, but he gets a decent scene with the alien later (although largely it feels like he’s just softening her up for Avon’s killer blow). Dayna gets to warble a tune(!) whilst Vila’s conjuring tricks (with a dose of non-diegetic sound) ends up as a decidedly creepy moment.

Easy to see why this is a slightly marmite story, since it’s almost totally a tale of dialogue and concepts with little or no action. But I’m glad that Boucher took a chance on a television novice like Tanith Lee, as both of her B7 stories are ones which repay multiple viewings.

Ultraworld

Vila seems to have had a nervous breakdown, that’s the only possible explanation I can find for his behaviour in this episode (chuckling with Orac at a series of lame riddles and gags). One sample will suffice – “Where do space pilots leave their ships? At parking meteors”. True, in the end this becomes an important plot point, but it’s still incredibly lame (you can’t blame Michael Keating, he could only work with the material he had, but the script gives him little scope to portray Vila as anything over than a childish buffoon).

Jan Chappell, who spends most of the episode unconscious, also has limited room to shine. So with Vila out to lunch and Cally asleep, that leaves the trio of Avon, Tarrant and Dayna. This does have its compensations – especially as we’re treated to some typical Avon jibes (when Tarrant declares that he takes calculated risks, Avon counters “calculated on what? Your fingers?”). And with Avon sitting most of the second part of the episode out, this leaves Tarrant and Dayna at the forefront – it’s notable how Tarrant takes control (even if you sense he really doesn’t know what he’s doing).

Although Ultraworld had a fairly small guest cast, it doesn’t seem to have been a particularly cheap show. The modelwork is impressive (the huge pulsating brain is gloriously icky whilst the capture of the Liberator is another nice sequence – albeit a bit wobbly). Location filming at the Camden Town shelter also helped to create a sense of space.

Of course the story is a very silly run-around (Trevor Hoyle, like Tanith Lee, was a science-fiction novelist and a television novice, but their two S3 stories couldn’t be further apart – one was lyrical and layered, and the other was called Ultraworld). This is a story that you sense Hoyle wasn’t taking terribly seriously.

Especially played for laughs is the scene where the Ultras decide that Tarrant and Dayna should demonstrate the human bonding ceremony. Dayna seems up for it (“kiss me. Come on. I can’t be all that repulsive”) as she, ahem, sets to work on Tarrant. The way the Ultras are looking in (“has the bonding ceremony begun?”) sets the tone of this sequence.

Everything’s sorted out with embarrassing ease – Cally and Avon might have had their memories stolen but luckily Tarrant was able to find their data stores just lying about. A pity they weren’t swopped around, as an episode with Avon stuck in Cally’s body (and vice-versa) would have been very interesting.

It’s silly, but it’s fun.