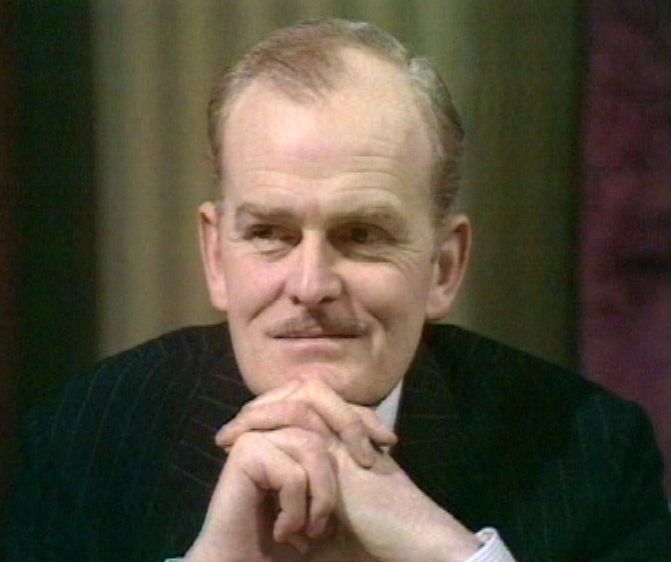

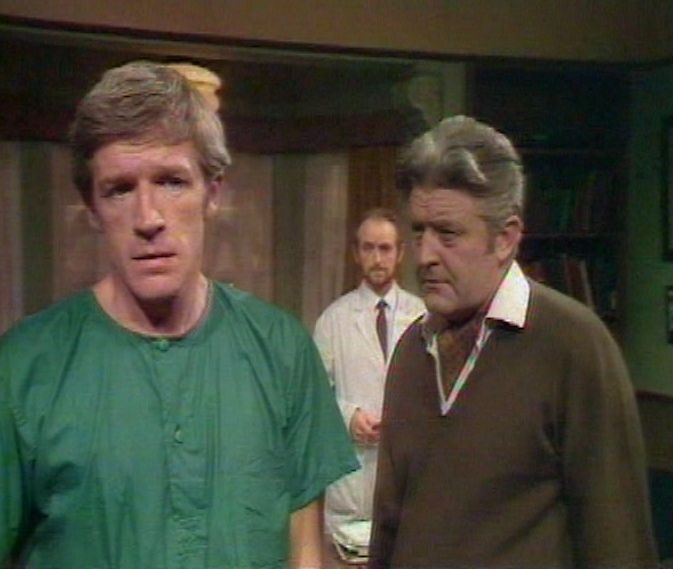

The Minister of Health (John Savident) and Duncan are ensconced on a health farm, located on a remote island. Quist is anxious to speak to the Minister as he needs an answer about the urgent flood problem, so isn’t best pleased to learn that the island has been placed in strict quarantine due to a suspected case of yellow fever.

Quist isn’t particularly interested in the yellow fever case, but it provides him with an excuse to travel over to the island with Fay to discuss the flood issue. The Minister’s a wily old bird though and he agrees to read Quist’s paper – as long as he helps the island’s doctors with the yellow fever outbreak. And it’s maybe just as well, as things aren’t as straightforward as they seem at first ….

Since this is a Gerry Davis script, it’s no surprise that it feels a little more like series one Doomwatch episode. Something happens for which there seems to be an obvious solution, but scientific detective work is able to prove otherwise.

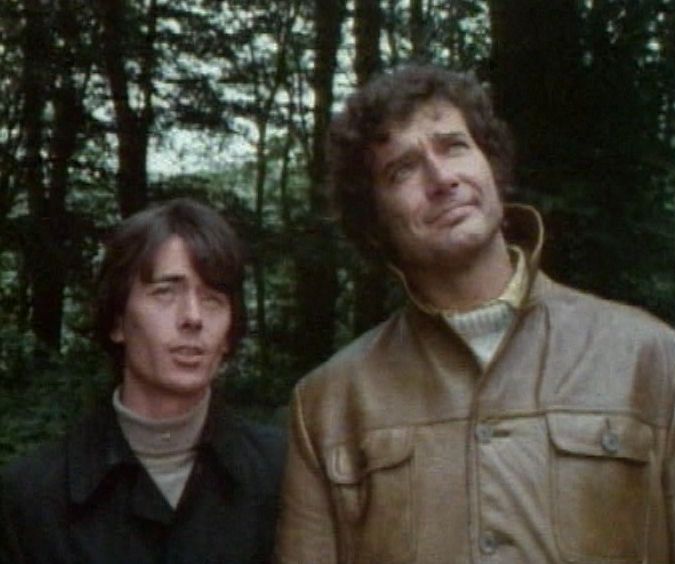

En-route to the island, Quist and Fay bump into the scientist Griffiths (Glyn Owen) and his wife Janine (Stephanie Bidmead). Quist knows Griffiths very well (as we’ll discuss in a minute) but Fay has never heard of him. Griffiths is keen to get to the island but is refused permission (although that doesn’t stop him, as both he and his wife charter a boat). One major weakness with the script is that Quist never seems to stop and wonder why a notable scientist like Griffiths is so keen to get to the island . Therefore it becomes clear to the audience much earlier than it does to Quist and the others that Griffiths unwittingly holds the key to the mystery.

Griffiths is a fascinating character, played with typical bluffness and spiky humour by Owen. Quist explains to Fay a little about his history. “He presented a paper at 2.00 pm at the Stockholm conference in ’65. By five o’clock it had been completely demolished. An elegant, almost perfect concept, ruined by inattention to detail.” Three scientists were responsible for pointing out several flaws which invalidated his paper (which had taken him fifteen years to prepare) and one of them was Quist. It’s a remarkable coincidence that they should now bump into each other again, but that’s television for you.

Although his life’s work was destroyed over the course of a few hours, Griffiths still doesn’t accept his research was flawed in any way, instead he still blames Quist and the others. This is why he’s kept his latest work under wraps and this secrecy will be the death of him (and others). It’s another sign that his researches are flawed – Quist tells Fay that a good scientist welcomes challenges to their theories (it helps them to refine and redraft) but the trauma of 1965 proved too much for Griffiths.

And what of Janine? Stephanie Bidmead and Glyn Owen share several well-crafted scenes that do nothing to advance the plot, but help enormously to bring their characters into focus. Janine shared Griffiths’ disappointment in 1965, but she’s been able to see that his paper was at fault and now she mourns less for him as she’s more concerned about the family they never had or the various other opportunities that passed them by, all because he was driven to chase something that always remained just out of his grasp.

The Web of Fear is a fairly bleak story although there are a few lighter moments. Ridge’s description of Janine always seems to move chestwards (“and she has a nice pair of …..”) whilst John Savident has a couple of comic moments. But the Minister, once he understands the gravity of the situation, is all business and is happy to back Quist once a solution is found.

What seems obvious from very early on is eventually confirmed. Griffiths’ latest work (a man-made virus designed to combat the moths which attack the island’s apple crops) is proved to be responsible for the apparent yellow fever attacks. Although the virus prepared by Griffiths only attacks moths, it can also trigger another virus in a new host. So the moth is ingested by a spider and the spider then becomes deadly. The attentive viewer would probably also have twigged this, as several times we hear different people commenting on how many spiders there seem to be – a good indication that this is an important plot point for later.

Griffiths is stuck down a tunnel and faces danger from both the spiders and their webs. Ridge elects to get him out and this forms the climax of the story, although it’s a little too drawn out for my tastes. Plus the over dramatic stock music saps the tension a little.

Another problem with this scene is that Griffiths dies off camera a few minutes later, which makes all the effort to rescue him something of a waste of time. But his death does allow Quist to give him a good eulogy. After Janine sadly reflects that her husband wasted twenty five years of his life and ended up with nothing – not even a decent reputation, Quist begs to differ. “He was a brilliant, intuitive scientist of the stamp of Pasteur, Einstein. The measure of the man is not that he failed, but that he so nearly brought it off. Twice.”

Although the story somewhat runs out of steam during the last twenty minutes or so, it’s still not a total write-off. Glyn Owen and Stephanie Bidmead both have well-written parts and the core team of Quist, Ridge and Fay work well together.