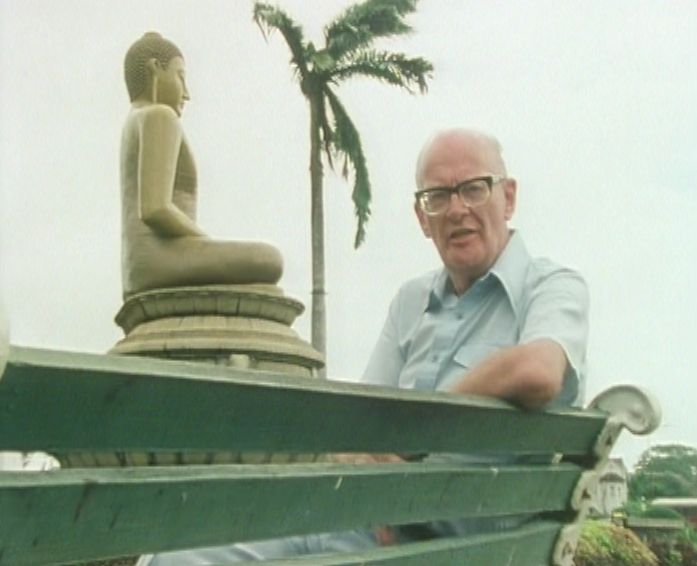

Ah Moloch. The one with Sabina Franklyn and the stupidest puppet alien you’re ever likely to see. It’s odd, but apart from those two facts I couldn’t remember anything else about the story prior to rewatching it. That’s surprising, since parts of the episode are certainly memorable (although not for the right reasons).

Avon’s been following Servalan’s ship for the best part of a month. Quite why he’s suddenly taken such an interest in her movements isn’t clear, although it seems to be simply because he’s got nothing better to do. In a way that sums up the actions of the Liberator crew during series three – a little light piracy here, some strange sci-fi adventures there, but as the Federation’s no longer the dominant menace it was you do get the sense they’re just marking time.

At the moment Vila’s taken over from Tarrant as the most annoying crewmember – no mean feat when you consider how irritating Tarrant can be. Vila spends the first scene moaning about the time they’ve wasted following Servalan (although since nobody pays him any attention he needn’t have bothered). If Michael Keating’s not best served by the start of the script then you have to give him full credit for throwing in a little bit of business as the Liberator looks set for a crash landing. Most actors would just stagger from side to side as the camera shakes, but Keating gives us a forward roll. Well done that man!

The planet, which turns out to be called Sardos, is initially depicted by a painting of some cliffs (with a little bit of smoke wafting across the screen). Clearly the budget had run out by this point, although they did manage to build one model set – showing Servalan’s docked ship – which looks quite effective.

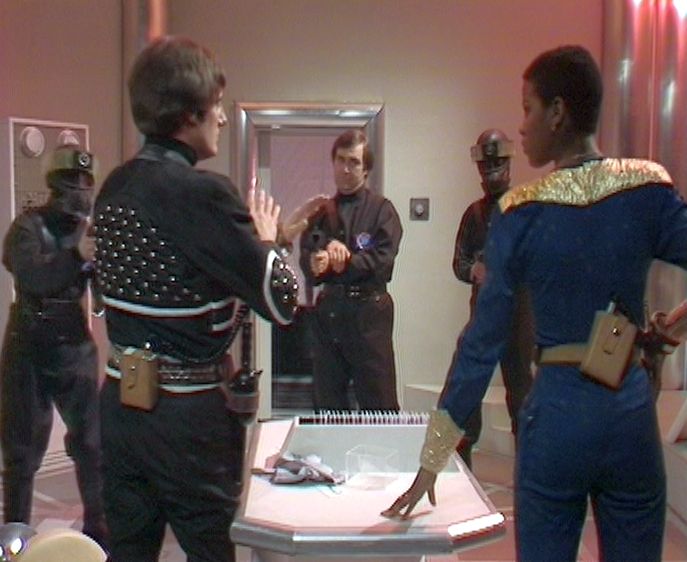

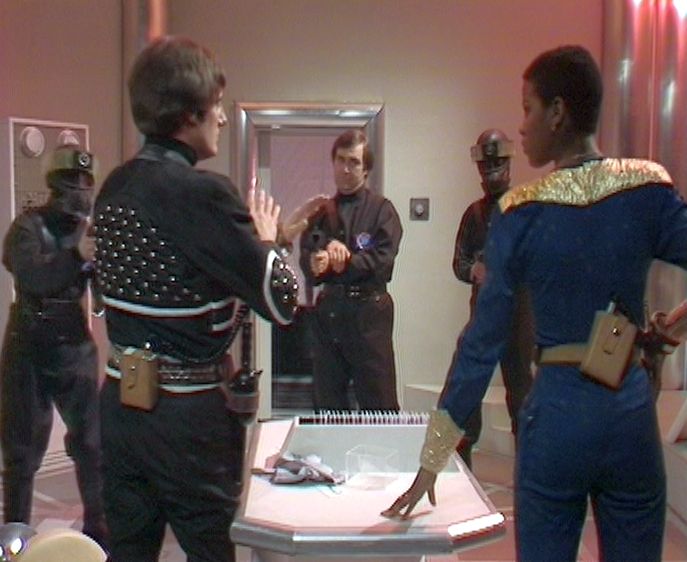

As it’s a Ben Stead script (writer, lest we forget, of Harvest of Kairos) it should come as no surprise that there’s more than a whiff of misogyny in the air. Poola (Debbie Blythe), Chesil (Sabina Franklyn) and the other women are depicted as little more than toys for the men to play with. After Poola spots the Liberator on a monitor screen she chooses not to report it, which incurs the wrath of Section Leader Grose (John Hartley). The unseen Moloch (voiced by Deep Roy) tells him that she must suffer and orders that she’s given to his men. Poola then receives a slap (albeit offscreen) although nothing else happens for the moment since Servalan then enters the room. Poola pleads with her for mercy – which the former Supreme Commander naturally ignores – and Servalan then sums up the state of affairs on Sardos rather succinctly. “Well, Section Leader, the records were accurate. Women, food, and inflicting pain – in no particular order.” This is jaw-dropping stuff.

Grose is, well, gross. As he enjoys a meal with Servalan and his second in command Lector (Mark Sheridan) he suggests that the attractive young waitress (no surprise that all the women are young and attractive) would look better with a “bit of dressing, and an apple between her teeth, eh?” He then slaps her on the backside just to drive the point home. Whether Ben Steed is satirising unreconstructed male attitudes to women or whether he’s approving of them is a moot point.

Vila and Tarrant reach Sardos by a circuitous route. They teleport onto a T-16 space transporter carrying a cargo of convicts and, as they make planetfall, Vila makes a new friend – Doran (Davyd Harris). Although he’s not quite the loveable rogue he appears. “Ahh, my problem was always women” he tells Vila. When Vila then asks if he likes them, Doran replies with a monosyllabic “no”. He’ll fit right in on Sardos then.

Things then lurch in an even more unexpected direction as Grose reveals to Servalan the secret of his power – an energy mass transmuter which “takes ordinary planetary matter – usually rock – and converts it into energy. The computer then restructures it into matter of every kind.” That Servalan finds herself completely outmanoeuvred by Grose does stretch credibility, although he does tell her that “if your reconstituted Federation was worth a light, you wouldn’t have chased halfway across the galaxy to retrieve one legion. Already I suspect my fleet outnumbers yours. Soon, it’ll be the most powerful in the galaxy.” It’s an interesting point, although this doesn’t quite tally with the impression given in previous stories that the Federation was slowly regaining its power.

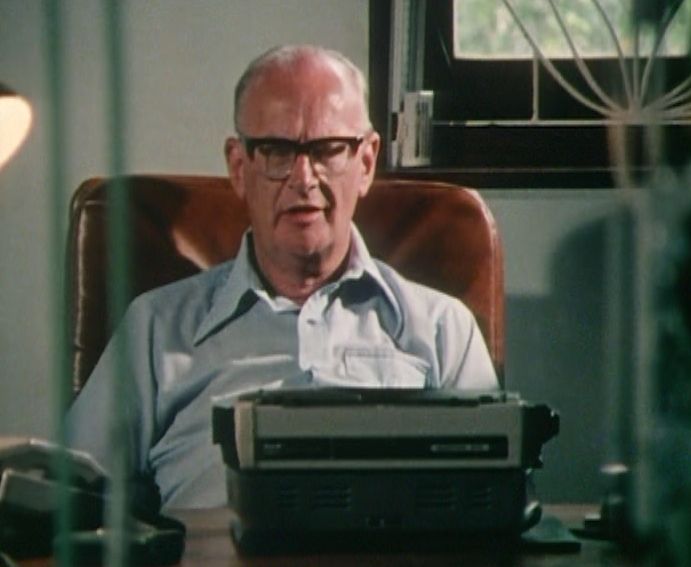

As we head into the last twenty minutes, things get funnier and funnier (although not always intentionally). Servalan is introduced to Colonel Astrid, Grose’s former commander. It’s difficult to find the words to describe the Colonel, but imagine a tatty doll suspended in water and you’ll get the idea. Moloch’s voice then pipes up and suggests that Servalan be given to Grose’s men. That seems to be all that Moloch does – recommend that misbehaving women be passed over to the men to be sorted out. Hmm, probably best to say nothing more.

Grose has been recruiting convicts like Doran to swell his ranks and Vila (his new best friend) has also been pressed into service. Doran tells Vila that he has a treat for him – a woman. That it turns out to be Servalan is an amusing reveal, as is the fact that they decide to briefly team up. Since Michael Keating and Jacqueline Pearce had rarely shared any screentime together, their odd-couple partnership is the undoubted highlight of the episode. A pity it couldn’t have lasted longer than a few minutes.

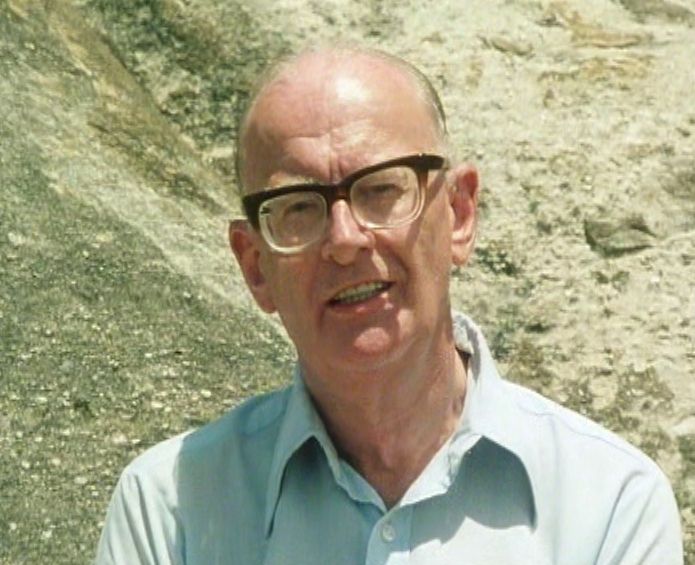

And then Moloch appears. “That is how I reasoned you would look” says Avon, incredibly. Mercifully he’s only onscreen for a brief moment although there’s also the spectacle of dead Moloch a few minutes later, which is even sillier than animated puppet Moloch.

Apart from all its other problems, the passivity of the female characters is a major negative. If at least one of them turned out to be a fighter and had helped to defeat Grose and his men that would have made some amends for the way they were treated. Chesil seems to be written that way – but right at the end she and Doran appear to be killed off. It’s never explicitly stated that they’re dead, but since we never see them again it’s a reasonable assumption.

Moloch is just bizarre. There’s the germ of a good idea – Servalan being held captive by a rogue section of the military – but the rest veers from the forgettable to the hilarious.