Ghost Light is definitely a story that’s bursting with ideas, although it could be that there were simply too many ideas and concepts for three episodes – as over the years many people have complained that the script is incomprehensible.

For me, whilst there are holes in the plot (although it’s hardly a unique Doctor Who story in that respect) the main thrust of the story and the performances have always been more than enough to draw me back to it. And often when re-watching, I’ll pick up on another aspect that I’d previously overlooked.

There are other Doctor Who stories from the original run which can be said to have rich subtexts buried under the visible plot-lines (Warriors’ Gate and Kinda for example) but these were pretty much the exception that proved the rule – generally Doctor Who stories from 1963 – 1989 operated on a very linear level.

Ghost Light doesn’t always adhere to this. Most of the answers are there (although you sometimes have to read between the lines) but some questions remain unanswered. For example, if we accept that Josiah was one of Light’s specimens who managed to escape from the stone ship in 1881 and sent the house’s owner, Sir George Pritchard, to Java, how has he managed to evolve so quickly? The evidence indicates that he was barely humanoid when he emerged (the husks) so it’s difficult to understand how he could evolve into a Victorian gentleman in a matter of a few short years. And how could Nimrod have evolved from a Neanderthal into the perfect butler during the same short space of time?

Some of these points probably explain why Ghost Light has remained a frustrating experience for some, but for me the first rate cast more than makes up for these unanswered questions.

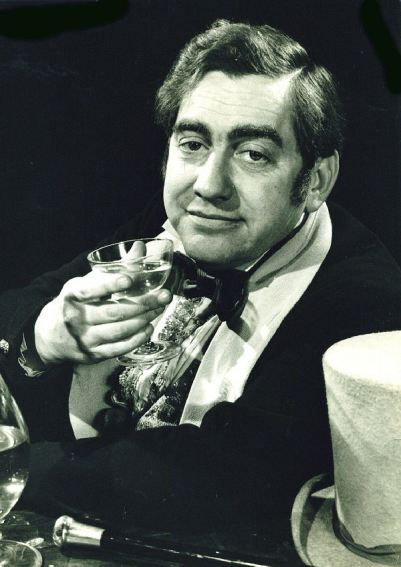

It’s probably the best-cast McCoy story. Ian Hogg (a familiar face at the time from Rockliffe’s Babies) is wonderful as Josiah, managing to turn from menacing to pitiful at the drop of a hat. Sylvia Syms has more of a one-note character for the majority of the story, although she does have a moment of tenderness in episode three (ironically just before Light deals with her). Katharine Schlesinger has a very fresh-faced appeal as Gwendoline. Although she and her mother were both under the control of Josiah, the Doctor delivers a rather chilling verdict about her, “I could forgive her arranging those little trips to Java, if she didn’t enjoy them so much”.

Michael Cochrane, Frank Windsor, Carl Forgoine and John Nettleton all add to the overall quality of the cast and the demise of Windor’s Inspector Mackenize gives us one of the great sick jokes of the series (“The cream of Scotland Yard”).

Sharon Duce is, interesting, as Control. It’s certainly a performance that’s somewhat at odds with the rest of the cast, but although she’s initially off-putting it does work better after a few re-watches. John Hallam is surprising fey as Light, but as with Duce it’s an acting choice that, after the initial surprise, does work.

Following Battlefield which didn’t do McCoy and Aldred any favours, they’re both back on top form in this story. With the Doctor deciding to take Ace back to the place where the ghosts of her past linger, this does put the spotlight on Aldred, which she’s more than able to deal with.

Maybe it was the studio environment or possibly the good actors around him, but McCoy’s at his best here. The clip below shows just how good McCoy could be. It’s slightly frustrating that he was rather inconsistent from story to story, but when he was good, he was very good.

If Light is defeated a little easily at the end (an occupational hazard of portraying powerful figures – the more powerful they are, the more of an anti-climax when they’re dealt with. See Sutekh for another example of this) it’s possibly more important that the Doctor has cured Ace of the lingering trauma she felt about the events of 1983.

From the moment we met her in Dragonfire, it was clear that Ace was something of a damaged character – and this is another example of the Doctor subtly sorting out her psyche. See also The Greatest Show in the Galaxy where he cured her fear of clowns and more seriously the upcoming Curse of Fenric where he attends to the tricky problem of her mother.

It’s possible to argue that the Doctor shouldn’t really be doing this, and it’s certainly not something he’s done before, but then he’s never really had a companion with quite so many problems as Ace. And her journey is all the more remarkable when you consider that Aldred only appeared in 31 episodes. Many companions have enjoyed far greater episode counts but few had the sort of character development enjoyed by Ace.

And her journey, central to this story, is one of the reasons why Ghost Light remains an outstanding example of late 1980’s Doctor Who.