Tanith Lee was a prolific novelist whose output covered many genres, including fantasy (both children’s and adult), science fiction, horror and historical fiction. Her two Blakes 7 scripts were her only ventures into television scriptwriting so it’s obvious that Chris Boucher took something of a chance when he commissioned her (writing a novel and writing a script are two very different disciplines).

We have to be grateful that Boucher did take the risk as Sarcophagus is unlike any previous Blakes 7 script. If you favour the action/adventure model of B7 then this one may not be to your taste – it’s a fantasy tale that includes a musical interlude and a dialogue-free opening scene featuring hooded characters performing strange acts. Although some of the plot elements are familiar – the Liberator spies a strange craft drifting in space/Cally gets taken over – Lee is able to take this hackneyed material and fashion something quite different from the norm.

Sarcophagus opens with a funeral aboard an alien vessel. Various masked characters perform different rituals – we see a musician, a soldier, a conjurer, etc – and later we see the Liberator crew dressed in the same garb, performing the same actions. The mysterious alien who takes over Cally’s body later reveals that she enjoys being attended to by intelligent minions, so it would appear that she is visualising how each of the crew would best serve her. No surprise that Vila is the jester or that Tarrant is the soldier (shoot first, think later seems to be his motto in this story). Unexpectedly, Dayna turns out to be musical (there’s a brief song mid-way through the episode, although this isn’t Blakes 7’s – The Musical, you may be glad to hear).

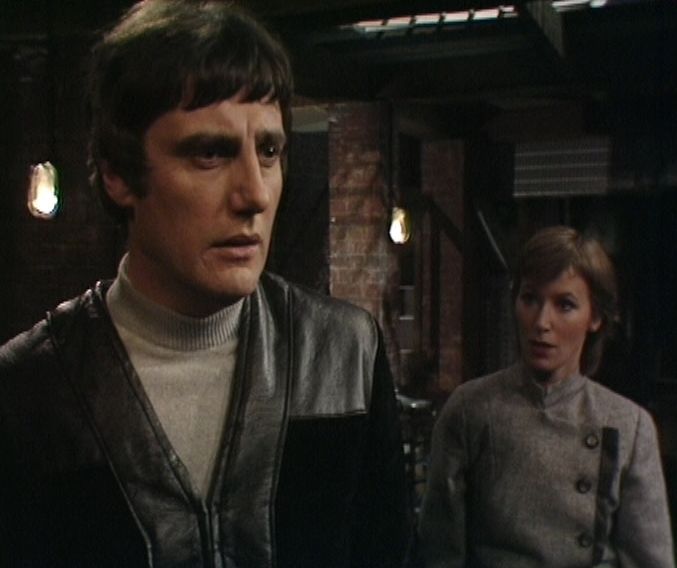

Since most of the action takes place aboard the Liberator and the only speaking roles are taken by the regulars, the script is a dense, dialogue heavy affair which has plenty of time to study how the various characters interact with each other. The relationship between Avon and Cally is key to the story and early on there’s a revealing moment in Cally’s cabin. She’s spent the last ten hours alone, thinking of her home planet and how she’ll never see it again.

AVON: I wish I could promise you that the sparkling company on the flight deck would take you out of yourself.

CALLY: I’m all right.

AVON: No, you’re not. But you will be. Regret is part of being alive. But keep it a small part.

CALLY: As you do?

AVON: Demonstrably.

Coming so soon after the events of Rumours of Death, it’s possible to argue that Avon’s referring not only to Cally, but also to himself. Either way, it’s a quiet, reflective moment that’s handled well by Darrow and Chappell.

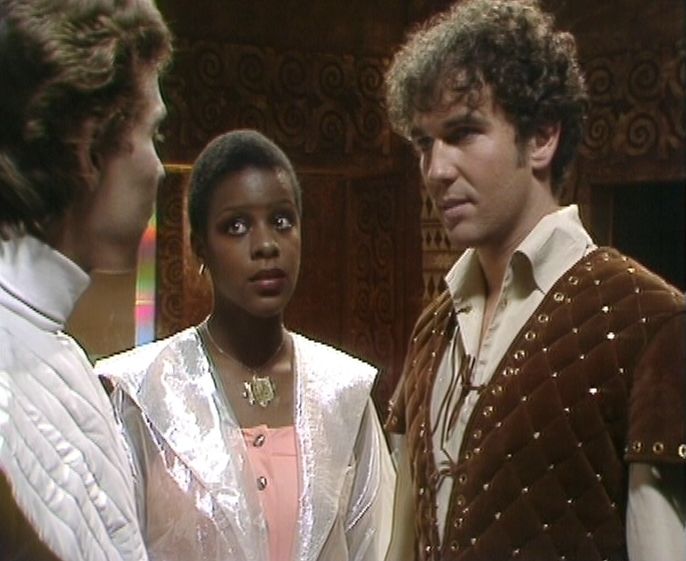

The most fun to be had comes from the clashes between Avon and Tarrant. Tarrant’s still being irritating and obnoxious – although he’s correct when he surmises that something came back with Cally from the alien vessel. It’s his bull-in-a-china-shop approach that wins him few admirers though.

AVON: Shut up, Tarrant.

TARRANT: Did you say something to me?

AVON: I said, shut up. I apologise for not realising you are deaf.

TARRANT: There’s something else you don’t realise. I don’t take any orders from you.

AVON: Well, now that’s a great pity, considering that your own ideas are so limited.

Darrow’s at his laconic best here, and it’s clear that Avon considers Tarrant to be no threat to his dominance at all (despite Tarrant’s claims to the contrary).

As the alien draws power from the Liberator, director Fiona Cumming elects to turn the lights down. This not only indicates that the ship is stricken, but it helps to increase the tension – which is furthered by the fact that both Orac and Zen are put out of commission. There’s something particularly disturbing about hearing Zen’s speech get slower and slower (he’s such a solid, reassuring presence that it’s jarring when he’s no longer there).

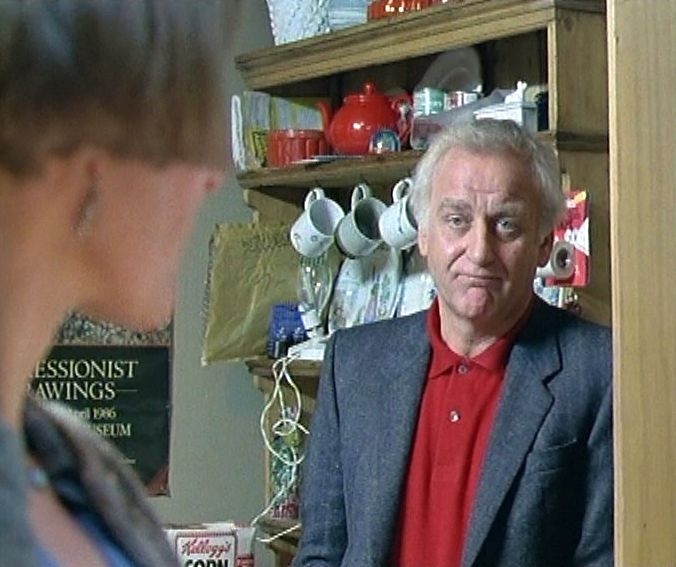

If the flashbacks (or flashforwards, maybe) of the Liberator crew dressed in strange costumes are odd, then even odder is Vila’s decision to do some conjuring tricks, mid episode, on the flight deck. It’s reasonable to assume that he decides to amuse himself in order to keep his spirits up (he’s alone and frightened of the increasing darkness) but after each trick there’s a massive round of applause. Do we suppose that this non-diegetic sound was only heard in Vila’s head? It’s only a throwaway moment but it’s another unusual, non-realistic touch.

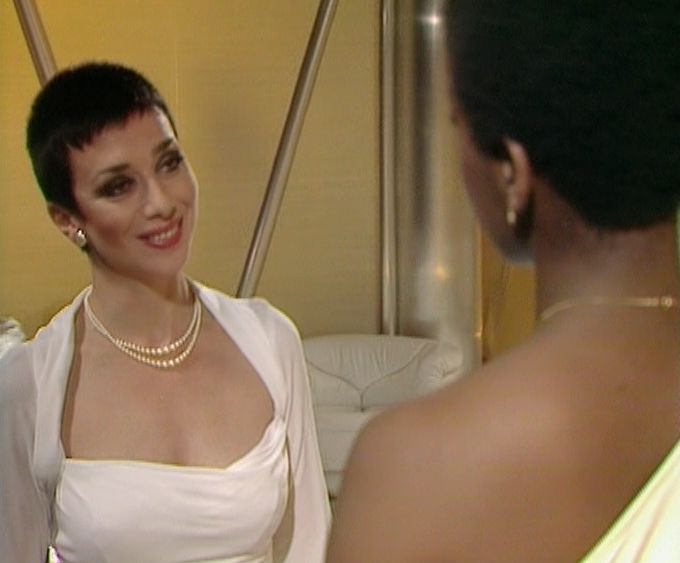

The alien who takes over Cally remains an indistinct character. We learn that for her race, death is merely an interim state and that she requires Cally’s body in order to attain corporeal form once again. She proves to be no match for Avon though – or rather it’s the part of her that’s still Cally who can’t bring herself to harm him. Unexpectedly he kisses her, although all becomes clear when he uses this as an excuse to wrench a ring from her finger. It’s the ring that’s allowed her to drain energy from Cally and when it’s removed, her power is broken. Darrow’s excellent again here as he refuses her entreaties to return it (“That would be a little foolish, when I just went to so much trouble to get it”) as is Chappell, as the alien senses her end is nigh.

Avon! Avon, give it back to me. You must. You don’t know. I HAVE to keep this body. I have to live. I’ve waited so long. Centuries. More time than you could comprehend. How can you imagine what it must be like to be dead, to exist in nothingness, in nowhere. Blind, deaf, dumb, and yet to be sentient, aware, waiting. Centuries of waiting. I have to find my world again, my people, my home. I want to breathe and see and feel. And know. Don’t send me back into the dark, Avon, let me live.

With a dual role for Jan Chappell, this is very much her episode but it’s equally a good vehicle for Paul Darrow. After a shaky few episodes early on, series three has hit a rich vein of form.