The previous episode ended with the Doctor being attacked by a mysterious assailant. It’s therefore something of a letdown to learn that it was only Ian – trying to warn the Doctor not to touch the controls, as they would have given him an electric shock.

Ian had two choices of course. Choice number one would have seen him tell the Doctor not to touch the controls whilst choice number two is to throttle the Doctor into submission. Yes, he goes for choice number two.

But why Ian would think the controls would be dangerous (and how he managed to awake from his drugged sleep) is a bit of a mystery. Yes, Susan was attacked by the console in the previous episode, but we saw the Doctor touch the controls later on with no ill effects.

For a few minutes, the Doctor is still convinced that Ian and Barbara are the cause of his problems, but eventually the penny drops that something is wrong with the ship. Barbara decides that the TARDIS has been trying to warn them. “We had time taken away from us and now it’s being given back to us because it’s running out” is just one of her baffling utterances which make no sense at all.

And the reason why the TARDIS acting so oddly? The Fast Return Switch was broken (a faulty spring!) and is hurtling the ship towards destruction. But rather than issue a conventional warning, the TARDIS decided that a series of oblique and bizarre moments would be just the ticket. Also, it’s impossible not to love the fact that somebody has written “fast return switch” in felt-tip on the console!

Hartnell has quite a long monologue which is designed to wrap the mystery up. Even at this early stage he was never keen on lengthy speeches – due to the worries he had with remembering lines. He is a bit wobbly in this story from time to time, but he’s pretty much perfect when it comes to this sequence. Although his reaction when receiving the script (“Christ! It’s bloody Hamlet!”) strongly implies that he needed some persuading to learn it!

I know. I know. I said it would take the force of a total solar system to attract the power away from my ship. We’re at the very beginning, the new start of a solar system. Outside, the atoms are rushing towards each other. Fusing, coagulating, until minute little collections of matter are created. And so the process goes on, and on until dust is formed. Dust then becomes solid entity. A new birth, of a sun and its planets.

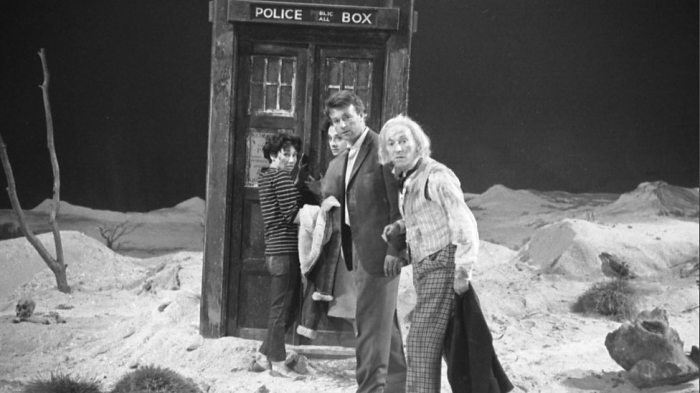

It was very possible that this would have been the final episode of Doctor Who. If so, then it would have ended with a more mellow Doctor finally beginning to appreciate his two new companions.

DOCTOR: I’d like to talk to you, if I may. We’ve landed on a planet and the air is good, but it’s rather cold outside.

BARBARA: Susan told me.

DOCTOR: Yes, you haven’t forgiven me, have you.

BARBARA: You said terrible things to us.

DOCTOR: Yes, I suppose it’s the injustice that’s upsetting you, and when I made a threat to put you off the ship it must have affected you very deeply.

BARBARA: What do you care what I think or feel?

DOCTOR: As we learn about each other, so we learn about ourselves.

BARBARA: Perhaps.

DOCTOR: Oh, yes. Because I accused you unjustly, you were determined to prove me wrong. So, you put your mind to the problem and, luckily, you solved it.

It also reinforces the notion that all four members of the TARDIS crew have something to contribute. It was Barbara who solved the mystery in this story, Susan returned to the TARDIS to fetch the anti-radiation drugs in The Daleks, Ian made fire in An Unearthly Child, etc.

This might be something of a ramshackle story, but at only two episodes it doesn’t outstay its welcome and apart from a few decent character moments it’s mainly memorable for the subtle reshaping of the Doctor’s character.