The second of Susan Pleat’s two scripts set in and around the geriatric ward, Concert, like Day Hospital before it, is an OB VT production shot on location. As previously touched upon, this helps to make the story seem just that bit more real. Sylvia Coleridge and Irene Handl return (the ranks of familiar senior actors is supplemented with the appearance of Leslie Dwyer) but it’s some of the background elderly players who, along with the location, are key to the documentary-like feel of the production.

They clearly are infirm and so don’t have to act the part. We see Shirley attend to them via a series of brief vignettes – fulsomely praising one lady after she walks a handful of steps to the table, gently cajoling another into taking a bite of food – and these moments spark mixed emotions. Shirley’s ever-growing connection to all her regulars is plain which makes her quick to react with anger when quizzed about the futility of looking after people who are clearly never going to get better.

This theme is developed when Jo, curious about the regular musical concerts organised in the hospital, decides to drop by and lend a hand. Jo’s reluctance to get involved with the geriatric side of nursing has been mentioned in previous episodes and is put into words today by another character. “Feed ’em and clean ’em and that’s your lot. They’ll addle your brains and break your back”.

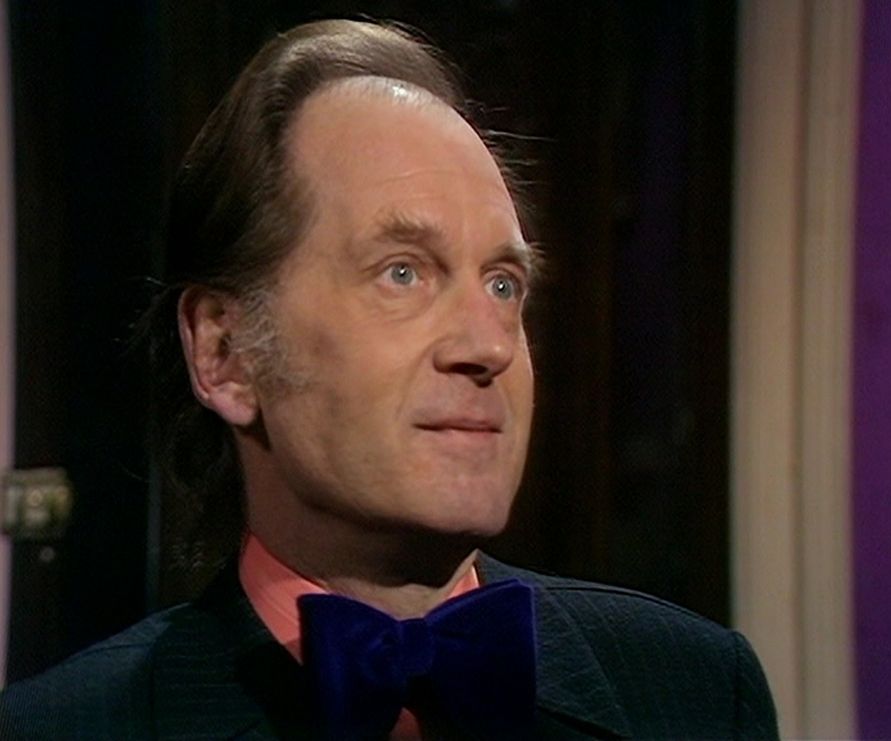

That seems to be a commonly held view and it’s the reason why many nurses elect to give geriatrics a miss. Concert, aiming to challenge this opinion, is helped by the fact that both Annie (Handl) and Patrick (Dwyer) are still mentally sharp, even if physically they’re beginning to fail. Their quick wits ensures that the viewer isn’t always dwelling on the frailer and more hopeless-looking cases.

But a feeling of melancholy is never far from the surface. At the same time that most of the old folks are having a jolly singalong at the concert (My Old Man being amongst the highlights) Ailsa, back in the ward, is being told by her son that they simply couldn’t cope with her at home. She, naturally enough, descends into bitter tears whilst elsewhere Jim Murphy (Colin Higgins) lectures Jo about the growing population of old people and the issues with caring for them.

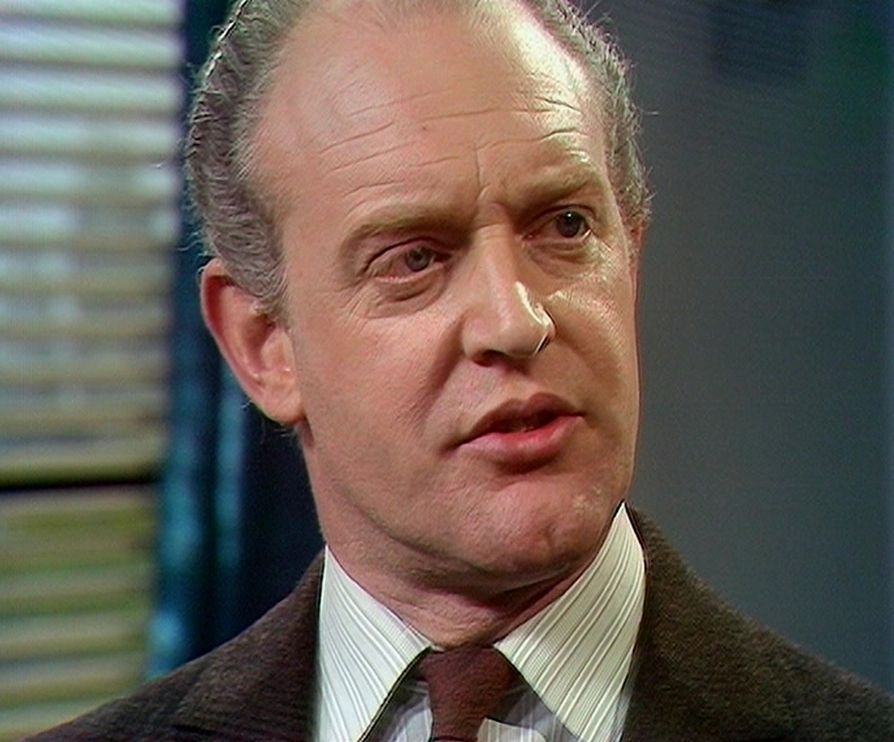

The series didn’t often take the opportunity to revisit one-off characters. They do today though, with Gordon Massey (Colin Higgins) making a return (he’d previously featured in the series one episode Saturday Night). He doesn’t have a great deal to do in this episode (and there’s no particular link back to his previous appearance) but it’s still a nice touch. Like Shirley, he’s passionate about his work on the geriatric ward – for him it’s because he knows what it’s like to be abandoned and therefore is adamant that it’s not going to happen to any of his charges.

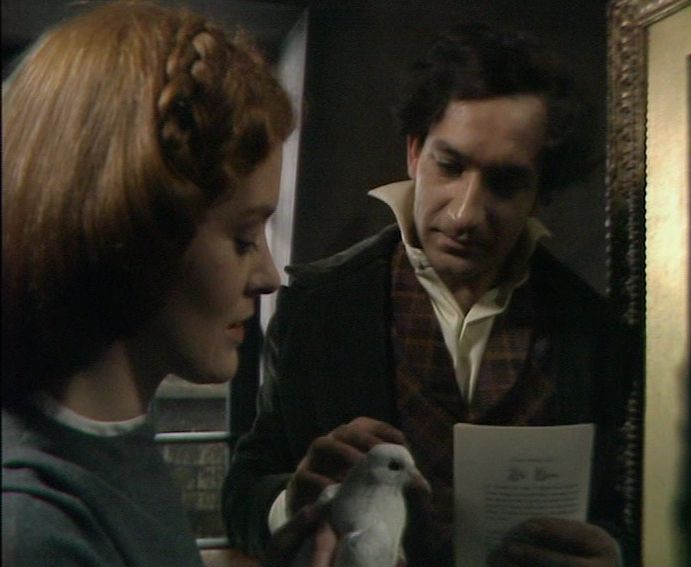

No doubt Shirley would have loved to have been at the concert as well, but instead she’s sharing an evening from hell with the drippy Roland (Norman Tipton). Quite what their previous relationship has been isn’t too clear, but Roland – shortly to depart for a lengthy trip abroad – is keen to demonstrate to Shirley just how much he cares for her. However it’s pretty obvious that the sooner he packs his bags and leaves, the better off she’ll be. Shirley may usually be bereft of male company, but you have to draw the line somewhere ….

It’s bad enough when he’s attempting to force wine on her at the restaurant, but things get even more toe-curling when he decides that playing a deep and meaningful record on her Dansette is the way to go. Not a good move. He may feel unfulfilled due to a lack of personal contact, but Shirley doesn’t. She has her work, and that is her life.

When they can’t talk very much, or even talk at all, they can’t hear you, well then you really have to look at them. Because people’s eyes are really where they are. And if I have to talk to them in that way, then I can. But, say with you or my mother then I can’t do that at all. Or with a lot of people. But there I just get on with things. It’s me and it’s right somehow.

This is a nicely delivered monologue by Clare Clifford, which sees Derek Martinus flicking back between close-ups of her and Norman Tipton (an ironic touch, given Shirley’s comment about people’s eyes).

Concert may have a lecturing tone, but it isn’t done in a heavy-handed way. Jo, like the audience, is pitched into a strange new world and by the end she seems to have learnt something, although there’s still a sense that she’s reluctant to get too involved, unlike Shirley. The episode doesn’t offer any pat solutions (given how complex the issues are, how could it?) but plenty of food for thought is generated.