Lord Longford was a tireless supporter of prisoner’s rights. He believed that nobody was beyond redemption, but his dogged campaign to secure Myra Hindley’s release only served to bring him savage public vilification ….

Even after all these years, the Moors Murders remains a dark stain on the British psyche. And if this horrifying legacy still resonates today, how much more powerful must it have been in the late 1960’s, when Lord Longford visited Myra Hindley for the first time? But despite being dubbed by the tabloids as “Lord Wrongford” he wouldn’t be swayed and carried on tirelessly pleading her case for decades.

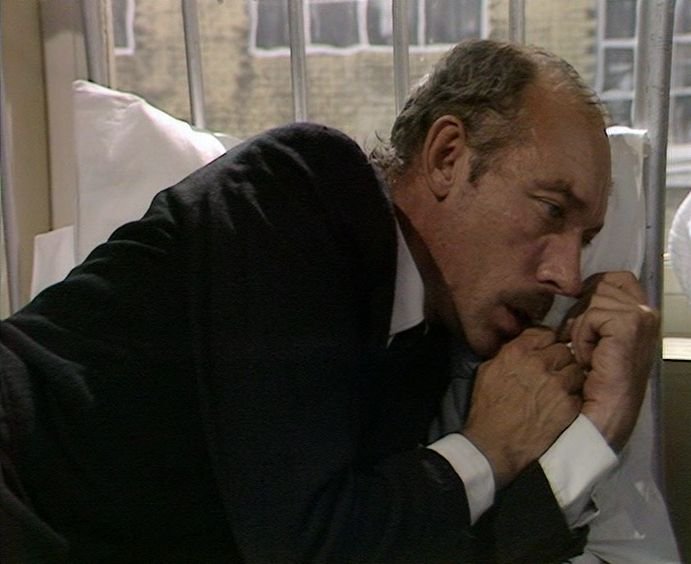

Even though he had to submit to several hours of prosthetic make-up each day, Jim Broadbent’s beautifully nuanced performance as Longford is nothing less than quietly stunning. It’s left to the audience to decide whether Longford was a good, innocent man or simply a gullible fool (or a little of both possibly). Broadbent certainly deserved all the plaudits and awards which came his way.

No less compelling and fascinating is Samantha Morton’s performance as Myra Hindley. As much of a victim as the murdered children, or an equal complicit partner with Ian Brady? She certainly seemed like a reformed character in Longford’s presence, but was that simply a ruse to gain his trust? As the film continues we begin to get an idea of the truth and Morton’s quiet, unshowy playing becomes increasingly more memorable.

Ian Brady’s evil is palpable though. Andy Serkis’ screentime might have been limited but he is still able to create a deeply unsettling atmosphere which lingers even after he’s left the screen. Brady’s first meeting with Longford is a typical snapshot of the short time they spent together. “How good of you not to disappoint! Wonderful, isn’t it, when people look exactly as you imagined? So this is my competition? This is what I’m up against? Myra’s new boyfriend? She certainly picks them, doesn’t she? I did a little research before our first meeting. I’d say there’s great evidence of mental instability in your past and mine”.

Brady’s contention that Hindley destroyed ‘him’ is intriguing. An example of Brady’s manipulative skill, or does the comment contain a kernel of truth? “Take my advice. Go back to your other prisoners. Nice, uncomplicated ones with broken noses and knuckle tattoos. Stay clear of Myra, because she will destroy you. Certainly destroyed me. That’s a thought you’ve not had before – that Myra egged me on”. Before Brady’s furnace of hatred, the affable and kindly Longford could do little but wilt.

Later events, such as Hindley’s confession to several subsequent murders (which she did in order to trump Brady’s own pending confession) wasn’t enough to totally destroy Longford’s faith in her, nor was her description of the first murder. “I’m trying to know the God that you know. But if you had been there, on the moors, in the moonlight, when we did the first one, you’d know that evil can be a spiritual experience too”.

Scripted by Peter Morgan (also responsible for The Last King of Scotland, The Queen, Frost/Nixon and The Damned United) Longford is a concise ninety minute teleplay which doesn’t contain an ounce of fat. Strong supporting performances help (most notably Lindsey Duncan as Lady Longford) as does the inclusion of genuine archive television reportage. In certain clips (for example, where the real Lord Longford appeared alongside David Frost and Lord Hailsham) a skilful spot of editing ensures that Broadbent replies to the archival comments of Frost and Hailsham.

Posing the difficult, if not insoluble, question as to whether forgiveness should be extended to everyone, regardless of their crimes, Longford offers no easy answers but plenty of food for thought and therefore stands as an absorbing drama which repays repeated viewings. Highly recommended.

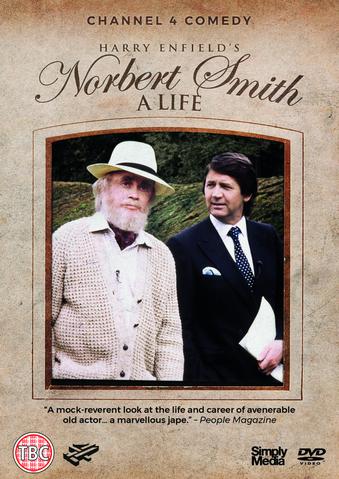

Longford is released today by Simply Media, RRP £14.99. It can be ordered directly from Simply here – quoting ARCHIVE10 will apply a 10% discount.