So after six and a bit episodes, the identity of the mole is revealed. It’s interesting that they didn’t pad it out until later in the episode, instead the reveal happens at the ten minute mark. Peter Guillam displays understandable anger at the lives lost. “You butchered my agents… How many since? How many? Two hundred?… Three?… FOUR?” Smiley remains calm, although in his own undemonstrative way he does display the odd spasm of anger later on.

So Gerald the mole was Bill Haydon. Smiley contacts Lacon, Alleline, Bland and Esterhase and plays them the incriminating recording which proves Haydon’s guilt.

Esterhase: Well, that’s that. Congratulations, George.

Lacon: Next step, gentlemen?

Smiley: Would you agree with me, Percy, that our best course of action is to make some positive use of Bill Haydon? We need to salvage what’s left of the networks he’s betrayed.

Alleline: [weakly] Yes…

Smiley: We sell Haydon to Moscow Centre for as many of our men in the field as can be saved – for humanitarian reasons. Professionally, of course, they’re finished.

Alleline: Quite.

Smiley: Then the sooner you open negotiations with Karla, the better. Well, you’re much better placed to talk terms than I am. Polyakov remains your direct link with Karla.

Lacon: The only difference is, this time you know it! It’s definitely your job, Percy. You’re still Chief, officially… for the moment.

Percy Alleline: Very well, George.

It’s a moment of triumph for Smiley, but there’s no overt display of emotion or triumphalism. Indeed, as we’ll see, it’ll turn out to be something of a pyrrhic victory although as the above dialogue extract indicates, he must have displayed some pleasure in Alleline’s discomfiture, who is clearly on borrowed time as Chief.

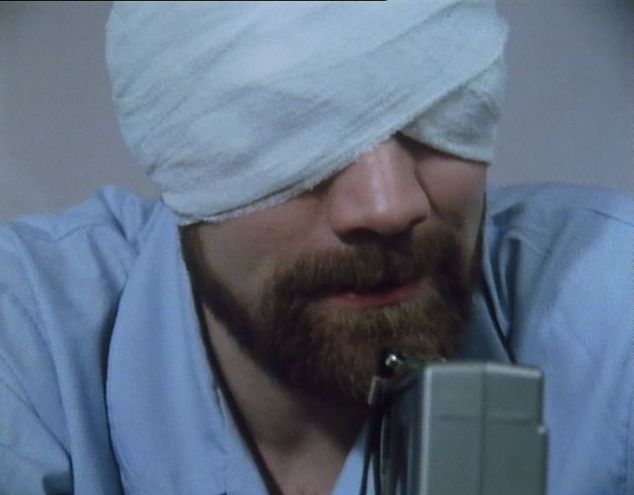

Before Haydon is sent back to Moscow, the interrogators are keen to extract every piece of information they can. The next time we see him, his face is covered in bruises, there’s blood on his shirt and he’s walking unsteadily – a clear sign of how he’s been “encouraged”.

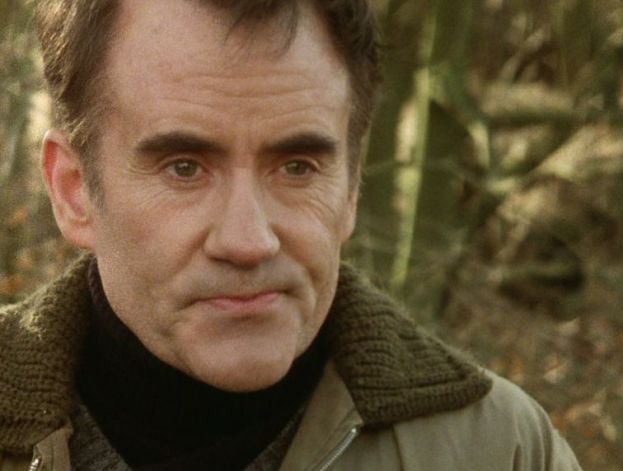

It’s felt that he may open up more to Smiley, and in a way he does. This enables Guinness to take up his usual role as the largely unspeaking observer – but it’s nevertheless quite easy to understand exactly what he thinks and feels just by the expressions on his face. Ian Richardson takes centre-stage in these scenes as he explains why he became a Russian agent.

Haydon: What do you want to know?

Smiley: Oh… why? How? When?

Haydon: Why? You ask that? Because it was NECESSARY, that’s why! Someone had to! We were bluffed, George. You, me, even Control. Those Circus talent spotters, all those years ago. They plucked us when we were golden with hope, told us we were on our way to the Holy Grail… freedom’s protectors! My God! What a question… “why?”

Smiley learns that when Haydon had the affair with Ann, it was on Karla’s orders. He also keen to know about whether Haydon expected Jim Prideaux to be sent on the abortive Czechoslovakia operation. As the friendship between Haydon and Prideaux has been stressed several times, there’s an undeniable sense of emotion as he replies to Smiley’s questioning.

Smiley: Did you expect Control to send Jim Prideaux?

Haydon: Well… obviously we needed to be certain Control would rise to the bait. We had to send in a big gun to make the story stick, and we knew he’d only settle for someone outside London Station, someone he trusted.

Smiley: And someone who spoke Czech, of course.

Haydon: Naturally. It had to be a man who was old Circus, to bring the temple down a bit.

Smiley: Yes, I see the logic of it. It was, perhaps, the most famous partnership the Circus ever had: you and him, back in the old days. The iron fist, and the iron glove. Who was it coined that?

Haydon: I got him home, didn’t I?

Smiley: Yes. That was good of you.

The clearest sign that Haydon has got under Smiley’s skin is demonstrated by the angry way Smiley opens the door after he’s finished his questioning. A small moment, like many of Smiley’s brief displays of anger, but it’s quite telling.

Haydon never made it back to Moscow, he was murdered before the exchange could be made. The novel implies (but doesn’t overly state) that Jim Prideaux killed him, the television adaptation is a little clearer on this point.

This leaves a final scene, which effectively acts as a coda, in which Smiley and Ann discuss her latest (completed) affair as well as Bill Haydon. She tells Smiley that she never loved Bill, and her final words “Poor George. Life’s such a puzzle to you, isn’t it?” is a bittersweet ending to an exceptional drama serial.