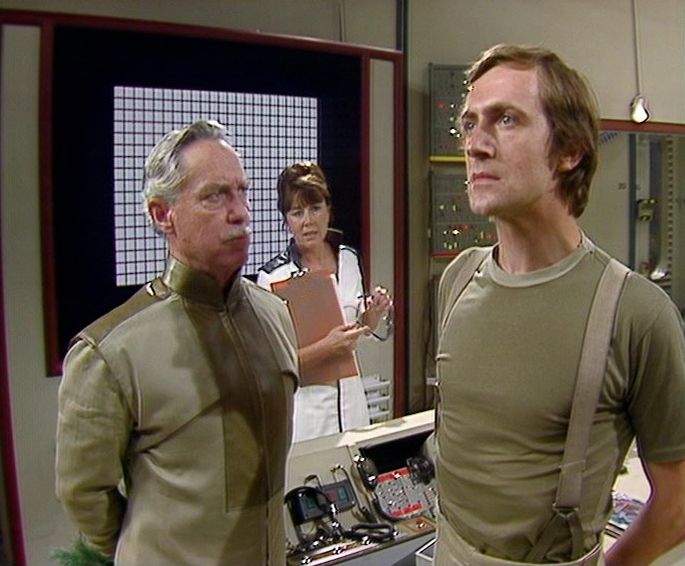

It’s fair to say that by Talons, Tom Baker’s Doctor has become something of a tyrant. Breezing through the story with an air of disdain, the Doctor might interact with the likes of Leela, Jago and Litefoot, but it’s rare that he ever seems interested in their opinions – this is a Doctor who always knows best.

How much of this was due to the scripting and how much was Tom Baker’s own input is a moot point. His dislike of Leela’s character is well-known (his personal relationship with Louise Jameson was also strained at the time) so it seems possible that some off-screen antipathy was bleeding onto the screen. But since the S14 Doctor is still far less objectionable than the breaktakingly rude Pertwee model from S8 it’s never been too much of an issue for me.

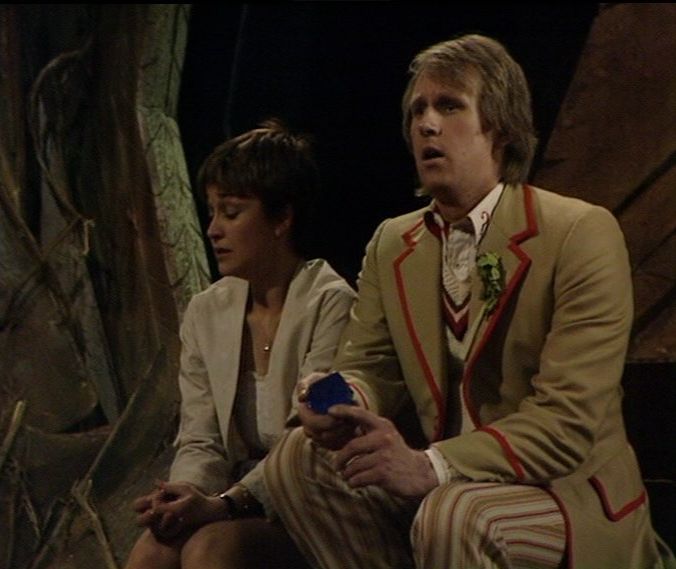

The attack on Litefoot’s house (an unsuccessful attempt to obtain the Time Cabinet) has two consequences – it takes Leela away from the Doctor’s side and puts her on a collision course with Greel as well as teaming the Doctor and Litefoot up as they attempt to locate Greel’s lair.

Since the Doctor’s dressed as Sherlock Holmes, it’s hardly surprising that he’s now been given his Watson subsistute in Litefoot. I surely can’t be the only person to wish that when Tom tackled Sherlock Holmes a few years later in the Classic Serial adaptation of The Hound of the Baskervilles, Trevor Baxter had been cast as his Watson. A missed opportunity alas.

Holmes (Robert, rather than Sherlock) always delighted in expressive language, as can be seen several times across this episode. The Doctor clearly has a low opinion of Greel and tells Litefoot why. “Some slavering gangrenous vampire comes out of a sewer and stalks this city at night, he’s a blackguard. I’ve got to find his lair and I haven’t got an hour to lose”.

Many were of the opinion that this era of Who wasn’t really suitable for children and when Chang abducts a prostitute (the latest intended victim for his master) you have to admit that they might have had a point. Once again, Holmes delights in a spot of ripe dialogue as Teresa tells Chang that her plans don’t include him. “As far as I’m concerned all I want is a pair of smoked kippers, a cup of rosie and put me plates up for a few hours”. Cor blimey guv’nor!

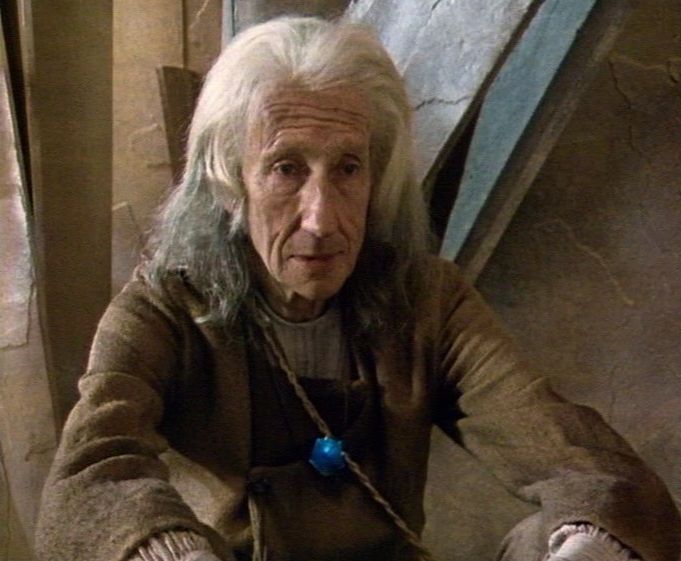

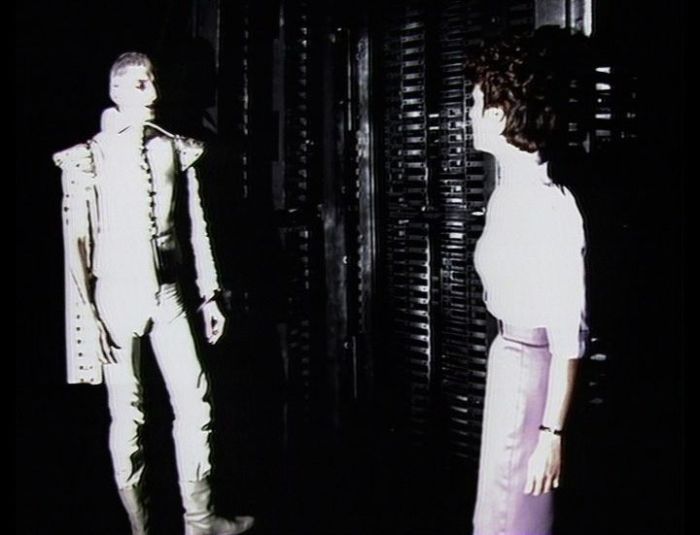

Although David Maloney was always a more than capable director – next to Douglas Camfield, he was probably the series’ best – the fight between Leela and Greel doesn’t quite convince. Possibly the studio clock was ticking, but Louise Jameson rather daintily steps around Greel’s lair (there’s little sense of a savage warrior here). In story terms, it’s also not quite clear why she heads out into the sewer – true, Greel did have a gun, but Leela’s the type likely to have pressed her attack on regardless.

Ah, the sewers. That means that giant rat is due to make another appearance. Poor Leela – reduced to her underwear, soaking wet and gnawed by a rat, so not her best day ever. And since Louise Jameson was suffering from glandular fever at the time it probably wasn’t one of her favourite days either.

At this point in the series’ history, it’s not a surprise that even the capable warrior Leela needs to be rescued. The Doctor’s on hand, with a Chinese fowling piece (made in Birmingham), but how good a shot is he?