The Sunday Night Theatre adaptation by Nigel Kneale of George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four (originally transmitted by the BBC on the 12th of December 1954) is a highly significant milestone in the development of British television drama.

Before looking at the programme itself, it’s worth taking a moment to consider the state of British television in 1954. The BBC had launched its television service in 1936, although its reach was initially extremely limited – only 20,000 viewers (those close to the single transmitter at Alexandra Palace) were able to receive the early television transmissions.

The outbreak of World War 2 in 1939 meant that the fledgling BBC TV output was suspended and it wouldn’t resume until June 1946. However, plans for the return of television had been discussed as early as 1943 and one of the major issues to be tackled was how to ensure that the whole of the country – not just those living in London – could view the service.

More transmitters were the answer. Sutton Coldfield in 1949, Holme Moss in 1951 and Kirk O’ Shotts and Wenvoe in 1952 ensured that a further twenty eight million people up and down the country could now access television. There were still gaps in coverage, which would be plugged as the decade progressed, but by the time Elisabeth II was crowned in Westminster Abbey on the 2nd of June 1953, BBC television had firmly established itself nationwide. By 1954 there were 3.2 million television licenses (a sharp increase on the 763,000 licenses registered by 1949).

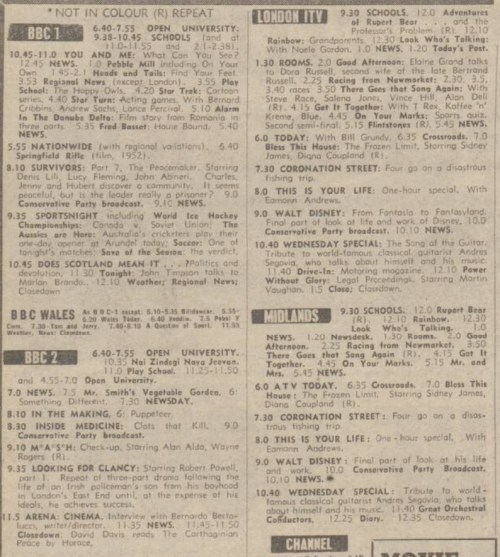

The launch of ITV in 1955 and BBC2 in 1964 were future milestones which would increase viewer choice – but when Nineteen Eighty-Four was broadcast in December 1954, British television was a one channel service, which meant that the BBC enjoyed the uninterrupted attention of the viewership.

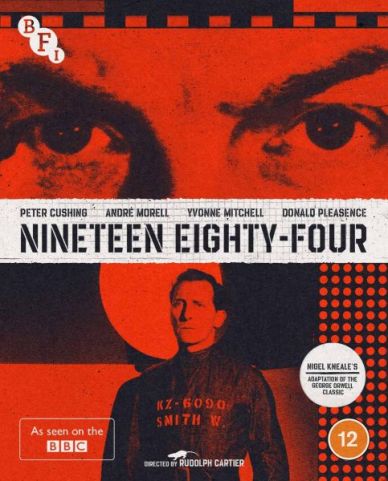

Nineteen Eighty-Four was adapted by Nigel Kneale and produced and directed by Rudolph Cartier.

Nigel Kneale’s (1922 – 2006) earliest BBC credits were on the radio. He appeared several times in the late 1940’s reading his own stories, such as Tomato Cain and Zachary Crebbin’s Angel. Graduating from RADA, Kneale continued to write in his spare time while pursuing an acting career.

After winning the Somerset Maughan award in 1950 for his book, Tomato Cain and Other Stories, he decided to give up acting to become a full-time writer. In 1951 he was recruited by BBC television to become one of their first staff writers. This meant that he would be assigned to work on whatever projects were in production – adapting a variety of books or plays for television broadcast. In 1952 he provided additional dialogue for a play called Arrow To The Heart. The play was adapted and directed by Rudolph Cartier and it would mark the start of a successful working partnership between the two.

Rudolph Cartier (1904 – 1994) was born in Vienna and initially studied architecture before changing paths to study drama at the Vienna Academy of Music and Dramatic Art. Cartier worked for German cinema from the late 1920’s onwards, first as a scriptwriter and then later as a director. After Hitler came to power, the Jewish-born Cartier moved to America to continue his film career.

However his success there was limited, so in the mid 1940’s Cartier moved to the United Kingdom and restarted his career by working as a storyliner on several British films. In 1952, Michael Barry was appointed head of Drama at the BBC and interviewed Cartier for a post as a staff television producer/director. Cartier was of the opinion that the current BBC drama output was “dreadful” and that a new direction was needed to turn things around. Fortunately Barry agreed and Cartier was hired.

After Arrow To The Heart, Kneale and Cartier would next work on The Quatermass Experiment (1953). This six part serial, scripted by Kneale and produced and directed by Cartier, would prove to be an enormous success. Its reputation has endured down the decades – The Times’ 1994 obituary of Cartier highlighted it as “a landmark in British television drama as much for its visual imagination as for its ability to shock and disturb.”

Kneale and Cartier would go on to make two further Quatermass adventures for the BBC – Quatermass II (1955) and Quatermass and the Pit (1958/59). Their other collaborations included another Kneale original, The Creature (1955), as well as adaptations such as Wuthering Heights (1953) and Moment of Truth (1955).

Published in 1949, Nineteen Eighty-Four by George Orwell offers a bleak dystopian picture of the future. The book is set in Airstrip One (formally Great Britain) which is part of the state of Oceania (there are two other states in the world – Eurasia and Eastasia). Oceania is constantly at war with one state whilst allied with the other. But since the allegiances are constantly changing, Oceania’s history has to be regularly re-written in order to maintain the omnipotence of Big Brother.

Winston Smith is a worker in the Ministry of Truth, rectifying “errors” in Big Brother’s previous pronouncements in order to ensure they now accurately record the “truth”. Winston’s desire to investigate the real past leads him to rebel against the state.

A popular and critical success when it was first published, Nineteen Eighty-Four was also a highly controversial book. So it was always going to be a difficult piece to adapt for television, particularly during the early 1950’s.

Peter Cushing (1913 – 1994) was cast by Cartier in the main role of Winston Smith. Cushing notched up an impressive series of television roles during the 1950’s, which would lead to Hammer Films approaching him towards the end of the decade to star in their adaptations of Dracula and Frankenstein, thus ensuring his celluloid immortality.

Yvonne Mitchell (who had appeared in the Kneale/Cartier Wuthering Heights) was cast as Julia, Andre Morell (later to play Professor Quatermass in Quatermass and the Pit) was O’Brien whilst the supporting cast included notable performers such as Donald Pleasance and Wilfred Brambell.

The music was composed by John Hotchkis. Cartier disliked recorded music, so the score was conduced live by Hotchkis in Lime Grove Studio E, next door to where the play was being performed. Hotchkis viewed the performance via a monitor in order to ensure that the music stayed in sync with the drama.

Prior to the first live performance on the 12th of December 1954, there was some pre-filming – initially on the 10th of November with additional filming taking place on the 18th of November. Pre-filmed inserts served several purposes – they could be used to present sequences that were impossible to realise in the studio but they were also useful for more practical reasons (allowing the actors time to move from one set to another or for them to make costume changes). The filming also helped to “open out” the drama, for example showing Winston moving through the prole sectors or Winston and Julia’s meeting in the woods.

Kneale’s adaptation remained pretty faithful to the original book, with only a few changes made (such as dropping the section where Julia, working in the PornoSec department, reads an excerpt from one of the erotic novels created by the machines).

Given the limitations of live production, this remains a striking piece of television. Cartier’s use of close-ups on Cushing (along with his pre-recorded thoughts) during the scenes where Winston is struggling to hide his “thought-crime”, allows the viewer an insight into his mind. And this is enhanced by Cushing’s fine performance – throughout the play he is never less than first rate.

He is matched by Andre Morell who as O’Brien exudes an air of cool detachment in all of his scenes (most famously during the torture sequence) which contrasts perfectly with Winston’s doomed humanity.

Probably the most striking aspect of the production, Winston’s torture is another part of the production handled very well by Cartier. The passage of time is signified by numerous fade-ins and fade-outs which helps to create the illusion that a considerable amount of time has passed. During these scenes, Morell is quiet, calm and reasonable, which is truly chilling. When the broken figure of Winston, stripped of all dignity, is led away it’s a shocking moment.

Following transmission, there was something of an outcry in certain quarters. Five MPs tabled an early motion, deploring “the tendency, evident in recent British Broadcasting Corporation television programmes, notably on Sunday evenings, to pander to sexual and sadistic tastes.”

However, an amendment to this motion was tabled, in which another five MPs deplored “the tendency of honourable members to attack the courage and enterprise of the British Broadcasting Corporation in presenting plays and programmes capable of appreciation by adult minds, on Sunday evenings and other occasions.”

The play did have supporters in high places though, as the Queen and Prince Philip had watched and enjoyed the production (although this wasn’t made public at the time) and newspaper commentary – from both columnists and viewers – ultimately evened out at around 50% in favour and 50% anti.

Videotape recording was still in its infancy at this time and whilst some telerecordings had already been made of live productions they weren’t always of rebroadcastable standard. For example, the first two episodes of The Quatermass Experiment had been telerecorded, but the results were judged to be disappointing and so it appears that recordings were not made of the subsequent four episodes.

The original transmission of Nineteen Eighty-Four was not recorded so, as was usual at the time when a repeat of a play was required, it was performed again. We are fortunate that the repeat was telerecorded, enabling us to have a record of the production.

A BD/DVD release of Nineteen Eighty-Four in the UK has been a long time coming. The story begins in 2004, when DD Video issued a press release, stating that a restoration of “exceptional quality” would shortly be issued on DVD. Then everything went quiet – reportedly the Orwell estate had exercised their veto to block the release.

Fast forward ten years to 2014, and this time a press release was issued by the BFI – as part of its Days of Fear and Wonder SF season, a restored DVD was reported to be on its way. But once again it never materialised, leaving us with the assumption that the Orwell estate had also blocked this one.

But since their copyright expired last year, they no longer have the power of veto – hence Nineteen Eighty-Four has eventually appeared on shiny disc.

Like Quatermass and the Pit, the 35mm film elements of Nineteen Eighty-Four still exist and, suitably cleaned up, they now look absolutely gorgeous (albeit with some intermittent tramlining). But it’s worth stating that the film element of the play is fairly minor, so the bulk of the production is obviously never going to look as good as the film work. The telerecording has scrubbed up pretty well though – there’s no doubt that it offers an upgrade from what’s previously been in circulation via the BBC2 and BBC4 repeats and foreign “bootleg” DVD releases.

This new restoration is enhanced by a number of special features. Jon Dear, Toby Hadoke and Andy Murray provide an entertainingly chatty commentary track which is packed with insight. Hadoke and Murray then return for a 72 minute in-vision discussion about Nigel Kneale and his legacy.

Slightly more digestible in a single sitting is The Ministry of Truth (24 minutes) a discussion between Dick Fiddy and Olivier Wake, in which the pair dispel some of the myths which have grown up around this adaptation of Nineteen Eighty-Four.

A 25 minute excerpt from Late Night Line-Up (1965) is of special interest – reuniting key members of the cast and crew for a roughly tenth anniversary retrospective. The package is rounded off with a handful of production stills, a PDF of the script and (available in early pressings of the disc only) an illustrated booklet with several short but informative essays. There’s also one other brief bonus feature, which wasn’t listed and therefore came as a very pleasant surprise.

Given the technical limitations of live performance as well as the primitive nature of a mid 1950’s telerecording, Nineteen Eighty-Four is still an incredibly compelling piece of television, thanks to all the performers, but particularly Cushing, Morrell and Yvonne Mitchell. Its place in the development of British television drama is a key one and anyone who has the slightest interest in the history of British television should snap it up.

Nineteen Eighty-Four – a dual BD/DVD release – is available now from the BFI and can be ordered via this link.