![dvd_snapshot_29.55_[2019.11.08_18.33.31].jpg](https://archivetvmusings.blog/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/dvd_snapshot_29.55_2019.11.08_18.33.31.jpg?w=700)

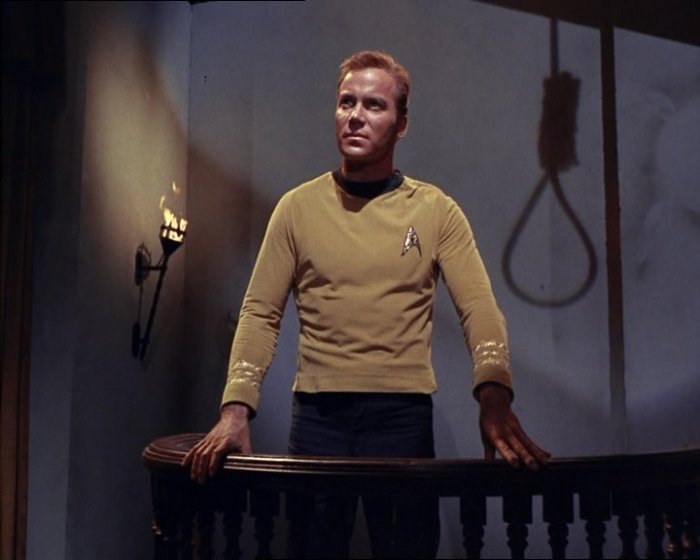

The Enterprise has travelled to Eminiar VII. Onboard is Ambassador Robert Fox (Gene Lyons), a man desperately keen to establish diplomatic relations with this mysterious and isolated planet. Kirk and a small landing party beam down, but whilst the locals are initially polite, the situation doesn’t stay stable for long.

Eminiar VII has been at war with a neighbouring planet, Vendikar, for five hundred years. The attacks may only be virtual (plotted by computer simulation) but the casualties are horribly real. Once the lists are totalled, the victims of each pretend attack have twenty four hours to present themselves to the nearest disintegration chamber.

The Enterprise has been declared a casualty of war, which means that every man and woman onboard is effectively dead ….

A Taste of Armageddon has an intriguing science-fiction concept, the problem is that it’s difficult to imagine any civilisation actually carrying such a crackpot scheme through (and for five hundred years no less). We’re told that three million people are sacrificed each year – multiply that figure by five hundred and it becomes even harder to believe.

I’m also mildly amused by the fact that each disintegration chamber only takes one person at a time. This must mean there has to be tens of thousands of them dotted around the cities – which is possible, if a little odd. Surely after five hundred years they would have come up with a more efficient way of culling their population.

Possibly if the war had only lasted twenty years or so and the casualties had run into the thousands rather than millions each year it would have been easier to stomach. But science fiction often likes to play with big concepts (it rather comes unstuck here though).

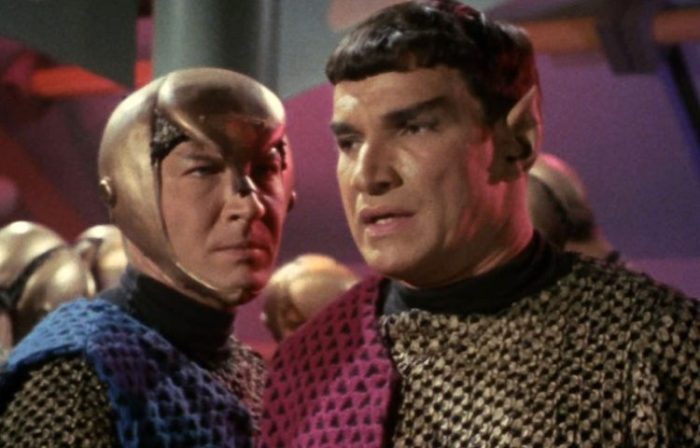

The fact that Eminiar VII is the planet of the silly hats is another problem, as is the total absence of any representatives from Vendikar. Apart from a number of non-speaking extras, Eminiar VII is represented by two people – the ruler Anan Five (David Opatoshu) and the rather attractive Mea 3 (Barbara Babcock).

This is obviously a bit limiting in terms of creating a picture of a rounded civilisation – Opatoshu is fine as the smoothly silky diplomat who nevertheless will do whatever it takes to keep the war on a level footing but Babcock is rather wasted in a role that doesn’t really go anywhere.

It’s not all bad though. Scotty being left in charge of the Enterprise is a real treat. As we’ve seen before, he’s a man who’s cool in a crisis (and is easily able to hold his own against the pig-headed Fox). Scotty’s mournful remark that “the haggis is in the fire now” after Fox threatens to send him to a penal colony for disobeying his orders is such a stupid line that I can’t help but love it.

William Shatner is a bit more staccato than usual, although Kirk does have some good scenes towards the end of the episode as he attempts to bluff Anan Five into capitulating by threatening to destroy the planet (or was he not bluffing?). Leonard Nimoy is also the recipient of a few nice little character moments, which helps to enliven the middle part of the episode.

The three redshirts who accompany Kirk and Spock down to the planet are incredibly anonymous. Yeoman Tamura (Miko Mayama) did catch my eye, but then she was very pretty ….

As I’ve probably said before, I like my Star Trek to err on the cynical side. A Taste of Armageddon fits the bill nicely in this respect – Ambassador Fox is a man prepared to do anything in order to establish diplomatic relations with Enimiar VII. Even if it means using force, no doubt. This paints the Federation less as an altruistic organisation dedicated to peaceful exploration and more as a military outfit keen to grab a foothold in a strategically important area of space.

Provided you don’t think about the plot too deeply, this is an episode that flits by in a very agreeable way. Yes, everything’s wrapped up a little too neatly – a five hundred year war sorted out by Kirk in a few minutes – but that’s the nature (and one of the drawbacks) of episodic television.

![dvd_snapshot_20.23_[2019.11.08_18.32.53].jpg](https://archivetvmusings.blog/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/dvd_snapshot_20.23_2019.11.08_18.32.53.jpg?w=700)